Joint Statement on Mosquito Control in the United States

Joint Statement on Mosquito Control in the United States from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Issued September 2012

The Role of Government Agencies and the Public

Mosquito-borne diseases are among the world's leading causes of illness and death today. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 300 million clinical cases each year are attributable to mosquito-borne illnesses. Despite great strides over the last 50 years, mosquito-borne illnesses continue to pose significant risks to parts of the population in the United States. Current challenges posed by the emergence of West Nile virus in the Western hemisphere illustrate the importance of cooperation and partnership at all levels of government to protect public health. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, the Agency) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are working closely with each other and with other federal, state, and local agencies to protect the public from mosquito-borne diseases such as the West Nile virus.

CDC, working closely with state and local health departments, monitors the potential sources and outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases and provides advice and consultation on prevention and control of these diseases. CDC works with a network of experts in human and veterinary medicine, entomology, epidemiology, zoology, and ecology to obtain quick and accurate information on emerging trends which they develop into national strategies that reduce the risk of disease transmission.

EPA ensures that state and local mosquito control departments have access to effective mosquito control tools that they can use without posing unreasonable risk to human health and the environment. EPA encourages nonchemical mosquito prevention efforts, such as eliminating standing water that provide breeding sites. The Agency educates the public through outreach efforts to encourage proper use of insect repellents and mosquitocides. Additionally, EPA's rigorous pesticide review process is designed to ensure that registered mosquitocides used according to label directions and precautions can further reduce disease-carrying mosquito populations.

State and local government agencies play a critical role in protecting public health from mosquito-borne diseases. They serve on the front line, providing information through their outreach programs to the medical and environmental surveillance networks that first identify possible outbreaks. They also manage the mosquito control programs that carry out prevention, public education and vector population management.

The public's role in eliminating potential breeding habitats for mosquitoes -- such as getting rid of any standing water around the home -- is a critical step in reducing the risk of mosquito-borne disease transmission. The public is also encouraged to make sure window screens and screen doors are in good repair. When venturing into areas with high mosquito populations, the public should wear personal protection such as long sleeve shirts and long pants, preferably treated with a repellent.. People should use mosquito repellents when necessary, and always follow label instructions.

Diseases Transmitted by Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes are found throughout the world and many transmit pathogens which may cause disease. These diseases include mosquito-borne viral encephalitis, dengue, yellow fever, malaria, and filariasis. Most of these diseases have been prominent as endemic or epidemic diseases in the United States in the past, but today, only the insect-borne (arboviral) encephalitides occur annually and dengue occurs periodically in this country. The major types of viral encephalitis in the United States include St. Louis, LaCrosse, Eastern equine and Western equine. These viruses are normally infections of birds or small mammals. During such infections, the level of the virus may increase in these infected animals facilitating transmission to humans by mosquitoes. The West Nile virus, which can also cause encephalitis, was found in the northeastern United States for the first time in 1999, is a good example of this mode of transmission. Human cases of encephalitis range from mild to very severe illnesses that, in a few cases, can be fatal. Dengue is a viral disease transmitted from person to person by mosquitoes. It is usually an acute, nonfatal disease, characterized by sudden onset of fever, headache, backache, joint pains, nausea, and vomiting. While most infections result in a mild illness, some may cause the severe forms of the disease. Dengue hemorrhagic fever, for example, is characterized by severe rash, nosebleeds, gastrointestinal bleeding and circulatory failure resulting in dengue shock syndrome and even death. Dengue is endemic in the Caribbean, Central and South America. Recently, dengue has occurred with increasing frequency in Texas. Other pathogens transmitted by mosquitoes include a protozoan parasite which causes malaria, and Dirofilaria immitis, a parasitic roundworm and the causative agent of dog heartworm. Disease carrying mosquito species are found throughout the U.S., especially in urban areas and coastal or in inland areas where flooding of low lands frequently occurs.

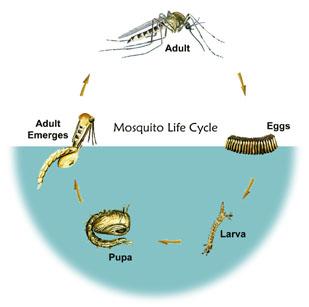

Mosquito Life Cycle

The life cycle of all mosquitoes consists of four distinct life stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult. The first three stages occur in water, but the adult is an active flying insect that feeds upon the blood of humans and/or animals. The female mosquito lays the eggs directly on water or on moist substrates that may be flooded with water. The egg later hatches into the larva, the elongated aquatic stage most commonly observed as it swims in the water. The larva transforms into the pupa where internal changes occur and the adult mosquito takes form. After two days to a week in the pupal stage, the adult mosquito emerges onto the water's surface and flies away. Only the female mosquito takes blood which they usually require for her eggs to develop.

The practice of mosquito control focuses on the unique biology and behavior of the mosquito species of concern. Mosquito biology can follow two general scenarios. The first involves those species that lay their eggs in masses or rafts on the water's surface. Some of these species, which are found throughout the U.S., often lay their eggs in natural or artificial water-holding containers found in the domestic environment, or in naturally occurring pools. The second scenario involves mosquitoes that lay their eggs on moist soil or other substrates in areas that will be flooded with water later. After about two days, these eggs are ready to hatch, but if not flooded, can withstand drying for months. In inland areas of the U.S. where these mosquitoes breed, heavy rains and flooding can produce millions of mosquitoes in a short time. Similar situations occur along coastal areas with mosquitoes adapted to salt marsh habitats. Some salt marsh mosquitoes are strong fliers and can sometimes travel up to 50 miles from the breeding site.

Mosquito Control Programs

In response to these potential disease carrying pests, communities organized the earliest mosquito control programs in the eastern U.S. in the early 1900s. Eventually, other communities created similar programs throughout the country in areas where mosquito problems occurred and where citizens demanded action by local officials. Modern mosquito control programs in the U.S. are multifaceted and include surveillance, source reduction, and a variety of larval and adult mosquito control strategies.

Surveillance methods include studying habitats by air, aerial photographs, and topographic maps, and evaluating larval populations. Mosquito control officials also monitor mosquito traps, biting counts, and complaints and reports from the public. Mosquito control activities are initiated once established mosquito threshold populations are exceeded. Seasonal records are kept in concurrence with weather data to predict mosquito larval occurrence and adult flights. Some mosquito control programs conduct surveillance for diseases harbored by birds, including crows, other wild birds, sentinel chicken flocks, and for these diseases in mosquitoes.

Source reduction involves eliminating the habitat or modifying the aquatic habitat to prevent mosquitoes from breeding. This measure includes sanitation measures where artificial containers, including discarded automobile tires, which can become mosquito habitats, are collected and properly disposed. Habitat modification may also involve management of impounded water or open marshes to reduce production and survival of the flood water mosquitoes. If habitat modification is not feasible, biological control using fish may be possible. Mosquito control officials often apply biological or chemical larvicides, with selective action and moderate residual activity, to the aquatic habitats. To have the maximum impact on the mosquito population, larvicides are applied during those periods when immature stages are concentrated in the breeding sites and before the adult forms emerge and disperse.

Some mosquitoes can fly from flood plains, coastal marsh areas, or protected habitats to impact urban residential areas. In these cases, it is often necessary to apply pesticides to kill adult mosquitoes. Surveillance data may prompt insecticide applications when mosquitoes are abundant. Applications usually coincide with the maximum adult mosquito activity in urban residential areas.

To be successful, mosquito control officials must apply insecticides under proper environmental conditions (e.g., temperature and wind) and at the time of day when the target species is most active. They must also apply these pesticides with carefully calibrated equipment that generates the proper-sized insecticide droplets that will impinge on adult mosquitoes while they are at rest or flying. If the droplets are too large, they will fall to the ground. If they are too small, the prevailing winds will carry them away from the target area. Once the insecticide spray mist dissipates, they break down in the environment (generally within 24 hours) producing little residual effect. Depending on the situation, mosquito control officials may safely apply these insecticides from spray equipment mounted on trucks, airplanes or helicopters. All insecticides used in the U.S. for public health use have been approved and registered by the EPA following the review of many scientific studies. The EPA has assessed these chemicals and found that, when used according to label directions, they do not pose unreasonable risk to public health and the environment.

Mosquito control officials have also developed water management strategies that take advantage of opportunities to maximize the impact of indigenous natural enemies to eliminate immature mosquitoes. The EPA and CDC encourage the use of these practices wherever they are environmentally sound, effective, and reduce pesticide use.

Integrated Pest Management

Mosquito control activities are important to the public health, and responsibility for carrying out these programs rests with state and local governments. The federal government assists states in emergencies and provides training and consultation in vector and vector-borne disease problems when requested by the states. The current interests in ecology and environmental impact of mosquito control measures, and the increasing problems that have resulted from insecticide resistance emphasize the need for "integrated" control programs. EPA and CDC encourage maximum adherence to integrated pest management (IPM). IPM is an ecologically based strategy that relies heavily on natural mortality factors and seeks out control tactics that are compatible with or disrupt these factors as little as possible. IPM uses pesticides, but only after systematic monitoring of pest populations indicates a need. Ideally, an IPM program considers all available control actions, including no action, and evaluates the interaction among various control practices, cultural practices, weather, and habitat structure. This approach thus uses a combination of resource management techniques to control mosquito populations with decisions based on surveillance. Fish and game specialists and natural resources biologists should be involved in planning control measures whenever delicate ecosystems could be impacted by mosquito control practices.

The underlying philosophy of mosquito control is based on the fact that the greatest control impact on mosquito populations will occur when they are concentrated, immobile and accessible. This emphasis focuses on habitat management and controlling the immature stages before the mosquitoes emerge as adults. This policy reduces the need for widespread pesticide application in urban areas.

EPA and CDC recommend that professional mosquito control organizations throughout the U.S. continue to use IPM strategies. Both agencies recognize a legitimate and compelling need for the prudent use of space sprays, under certain circumstances, to control adult mosquitoes. This is especially true during periods of mosquito-borne disease transmission or when source reduction and larval control have failed or are not feasible.

Education

To be of maximum effectiveness, the people, for whom protection is provided, must understand and support mosquito control. An integral part of most organized mosquito control programs is public education. It is important that residents have a good understanding of mosquitoes, the benefits realized from their control and the role people have in preventing certain mosquito-borne diseases. Being aware of pesticide application times is also important for individuals so they may decide on precautions they may need to take. While this usually involves education of the public through announcements in the media, some control programs have staffs that develop and present educational programs in public schools. People who are informed about mosquito biology and controls are more likely to mosquito-proof their homes, and eliminate mosquito breeding places on their own property.

For More Information

For more information about mosquito control in your area, contact your state or local health department. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is a source of information on disease control, and their Internet web site includes a listing of state health departments.

To contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

Telephone: 970-221-6400

Fax: 970-221-6476

E-mail: dvbid@cdc.gov

web site: https://www.cdc.gov

Information on pesticides used in mosquito control can be obtained from the state agency which regulates pesticides, or from the National Pesticide Information Center (NPIC) West Nile Resource Guide.Exit

National Pesticide Information Center

1-800-858-7378 - daily except holidays. Callers outside normal hours can leave a voice mail message.

E-mail: npic@ace.orst.edu

Web site: http://npic.orst.edu/ Exit

Information on mosquito control programs can also be obtained from the American Mosquito Control Association (ATop of PageMCA) website. This site also lists many county mosquito agencies.

For more information regarding the federal pesticide regulatory programs, contact:

EPA Office of Pesticide Programs

Ask a question

Website: https://19january2021snapshot.epa.gov/pesticides