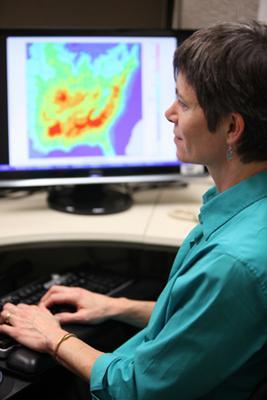

Meet EPA Chemical Engineer Deborah Luecken

Deborah Luecken is a research scientist who develops descriptions of the chemistry that occurs in the atmosphere to form ozone and other air pollutants. She works with a group of meteorologists, physicists, and chemists developing the Community Multiscale Air Quality Model (CMAQ), a computer model that can predict how air pollution is formed and transported in the atmosphere and is used to reduce pollution in the future.

How does your science matter?

I develop models that show how the chemistry in the atmosphere and sunlight affect concentrations of air pollutants. I focus on air pollutants that aren’t emitted from sources like cars or power plants, but that are formed in the atmosphere, which makes them harder to control. If a pollutant is coming right out of your car, you can put on a filter and stop it, but when it’s something that’s formed in the atmosphere, from multiple different chemicals, we have to first understand the chemistry that’s causing the pollutants to form before we can find the correct actions to reduce the pollution.

Ozone is a great example, and is one of the most pervasive and harmful pollutants in the U.S. Ozone isn’t emitted directly by cars, but pollutants that are emitted from cars go into the atmosphere and, under the right conditions, they can react to form ozone.

My group develops computer models that replicate the conditions under which ozone and other pollutants are formed and can predict what we need to do in the future to reduce pollution. Our work helps EPA develop optimum ways to improve air quality and ensure that the actions they take to reduce ozone and other pollutants are accurate, efficient and cost-effective.

If you could have dinner with any scientist, past or present, who would you choose and what would you ask him or her?

I would like to have dinner with chemical engineer Hannah Long because her quote, “there’s always something to be learned” perfectly describes the attitude that scientists – and all of us – should cultivate. I would love to have her on my team! I would ask about her experiences of being a young female engineer in the workforce and what we could do to increase the participation of women in STEM fields.

When did you first know you wanted to be a scientist?

I always figured I would do something in science, but wasn't sure what type of science. How are you supposed to know exactly what you want to do in high school?

In college, I started off with chemical engineering as a backup plan but wanted to explore other areas. I was a geologist, pre-med, chemist, even an art historian for a few weeks, but nothing else stuck. Once I figured out that I could do environmental work through chemical engineering, I was hooked.

What do you like most about your research?

Atmospheric chemistry is really fun. It's like working on an interesting, complicated, and constantly-changing puzzle. The concentration of chemicals in the atmosphere is different than it was twenty years ago. We learn more every day. The weather changes every day and that affects the chemistry. We discover new problems, too.

I also like knowing that the American people are my customer and my job is to make the air healthier for the public good.

Tell us about your science/educational background.

I have bachelors degrees in liberal arts from Oberlin College and in chemical engineering from Washington University. I also have a masters degree in chemical engineering from the University of California Los Angeles.

If you were not a scientist, what would you be doing?

I'd probably be an architect. It's similar to an engineer in that you have to look at all the different pieces of the puzzle and figure out the best solution. I'd like to build green buildings and figure out the most efficient way to create beautiful, healthy, low carbon footprint living spaces.

Any advice for students considering a career in science?

Don't give up early! Engineering is a lot of work in the beginning. It's not always obvious in some of the beginning courses why it is relevant, but when it all comes together, you'll find out you have all the skills you need to solve the big and interesting problems.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed herein are those of the researcher alone. EPA does not endorse the opinions or positions expressed.