Meet EPA IT Specialist Linda Harwell

Linda Harwell’s love for the ocean started at a very early age. As a Navy brat, Linda moved around a lot but she never lived far from a coast. Even now, working as an Information Technology Specialist at EPA’s research laboratory in Gulf Breeze, Linda gets to see the ocean right outside her office every day.

Tell me about your background Greetings from Florida! Meet EPA IT Specialist Linda Harwell.

Greetings from Florida! Meet EPA IT Specialist Linda Harwell.

I came to EPA in 1993 as a contractor and became federal employee in 1998. I was hired to assist with managing data for EPA’s Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Program, so I was in “science data management” before it was cool. One of the things I really love about working at EPA is that I’ve always worked in a team environment. It has allowed me to be engaged in the whole research process. Now, I don’t just do data management—I do data analysis, communication, report writing, and I recently started working on web content. It’s great because I get bored easily. Today, I work in a coordinated effort assisting the Office of Water with implementing the National Coastal Condition Assessment which is part of the National Aquatic Resource Surveys Program. I also work in three different areas under EPA’s Sustainable and Healthy Communities Research Program: The Human Wellbeing Index, Climate Resilience Screening index, and Ecological Relevance Index. I guess you could say that my expertise is in data wrangling and indicator development.

When did you first know you wanted to be a scientist?

It was the early 70s. I was enthralled with the TV series, The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau. I think everybody wanted to be a marine biologist after that show. It was just such a cool thing. It inspired me to become a certified scuba diver when I was 13. And that was before it was glamorous! The wet suits were so uncomfortable, you couldn’t put your arms down when you were wearing them. It was very much a brand new world for many people back then.

How does your science matter?

The science that I work in matters because we tackle large, complex questions. For example the condition of our coastal resources, how to measure well-being, etc. We use indicators to answer some of these questions. There is a lot of research effort that goes into synthesizing data into an indicator that is meaningful. Indicators help us engage people in the science EPA does and I think that’s really important. It makes scientific results interpretable for a broad audience.

What do you like most about your research?

The first is telling a story with research results. That’s probably one of the biggest things for me. The second is the diversity of my job. Over the years I have been afforded the opportunity to become more holistic in expertise. I get to participate in research from the concept to the product. I think a fully engaged team is really important. When research teams are inclusive, products are more robust, work flow is more efficient, and all team members have a sense of ownership. If one team member moves on, the work can continue without a hitch, at least for a while, because everyone has some knowledge about all the things happening in the research.

If you could have dinner with any scientist, past or present, who would it be and what would you ask them?

Alan Turing, who was instrumental for coming up with the computer that deciphered the Enigma code used against the allies during World War II. When I look at my computer, I see a box with a bunch of wires and electricity running through it. I know it helps me do my job faster and better, but that’s all I really see. He looked at the same thing and conceptualized a machine that could “think”. In many circles, the Enigma deciphering algorithms were sort of the early whispers of artificial intelligence. And he conceptualized it given only a box of wires and electricity! What did he see that others did not? How did he imagine it? If he was alive today, would he be excited or disappointed by how things have evolved?

If you weren’t a scientist, what would you be doing?

I’d work for the Humane Society. I’ve always had pets growing up. I have a really big soft spot for animals, especially those who need a safe place to call home. I’m a champion of any underdog.

If you could have one superpower, what would it be?

I’d like to be empathic, like the skill portrayed in Star Trek. To be able to change the tone and temper of my conversation to match the mood and feelings of those around me would be really awesome. I could help minimize misunderstanding. I could also engage others who feel like they’re being unheard. Or maybe just know when I need to be quiet.

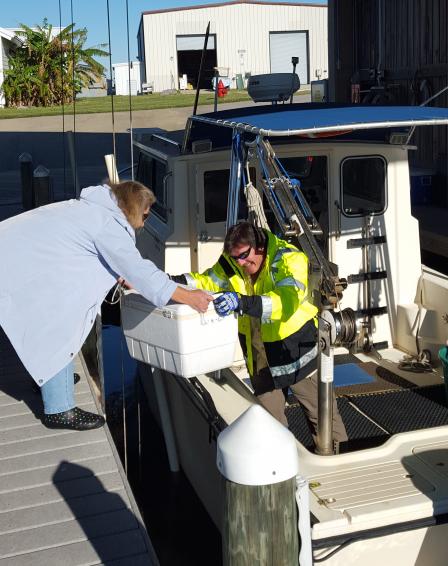

Harwell helps EPA's George Craven carry research equipment off of a boat. Do you have any advice for students considering a career in science?

Harwell helps EPA's George Craven carry research equipment off of a boat. Do you have any advice for students considering a career in science?

I always wanted to be a marine biologist but I went with computers because it seemed to be a more practical thing to do. Over time, it became clear that my affinity for the ocean was much stronger than my need to be practical. So I shifted my skills from finance to science and now I work as closely to aquatic science as I can. So my advice is find that dream and pursue it. Hang on to it. You may take many different turns you weren’t expecting, but if you hang in there the path will come around to where you want it.

What do you think our biggest scientific challenge is in the next 20/50/100 years?

Because I’m so keen on communicating research that I think our biggest scientific challenge is being able to properly and thoroughly educate the public about what it is our research is telling them. Particularly when it comes to things like climate change, environmental conservation, and environmental protection. What does all that mean to them? For a lot of folks, I think they see it as something intangible. They don’t see it as having a direct influence on them. And I’m a firm believer that change only happens through grassroots efforts. If one person does it, it’s not enough. But if the next person, and then the next person does it, it starts to have an effect.

Whose work in your scientific field are you most impressed by?

My background is really broad and there are so many, so it’s hard to choose just one. Recently, a group of scientists at the CERN Laboratory near Switzerland reportedly observed the Higgs boson particle. What caught my eye about this discovery was a particularly engaging communication piece that used animated drawings to describe the discovery, how it was made, and why we should actually care about it. When was the last time anyone did that for physics? Did the communication piece make me an expert in quantum physics? Of course not, but it did make me take a moment to learn more. Will the debate about the existence of the Higgs boson particle be a compelling discovery in the long run? Maybe, but I think the true power of any scientific discovery is that it sparks the imagination.

If you were stranded on a desert island with a group of other survivors, what would be your job?

I would be Team Mom! In team sports, the Team Mom is the one who does all the important stuff that no one remembers or cares to do.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed herein are those of the researcher alone. EPA does not endorse the opinions or positions expressed.