Why Wildfire Smoke is a Health Concern

This section of the course covers the following topics:

Wildfire Smoke: A Complex Mixture

Wildfire smoke is comprised of a mixture of gaseous pollutants (e.g., carbon monoxide), hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) (e.g., polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [PAHs]), water vapor, and particle pollution. Particle pollution represents a main component of wildfire smoke and the principal public health threat.

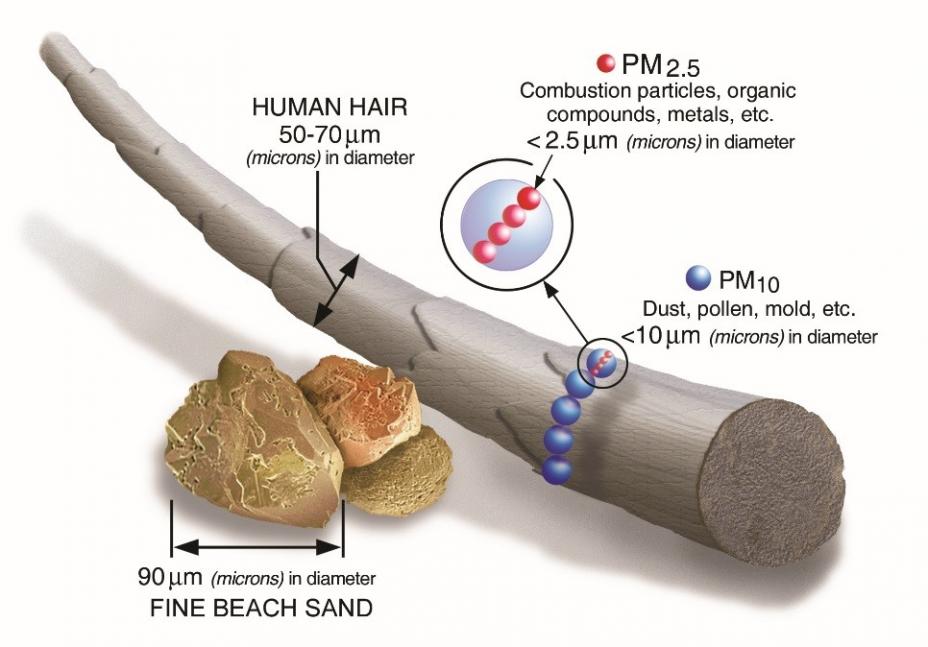

“Particle pollution” (also referred to as particles, particulate matter, or PM) is a general term for a mixture of solid and liquid droplets suspended in the air. There are many sources of particle pollution; the most common is combustion-related activities, such as wildfires. Because of the variety of sources, particles come in many sizes and shapes. Some particles are so small that they are only visible using an electron microscope (Figure 1). Particles can be made up of different components, including acids (e.g., sulfuric acid), inorganic compounds (e.g., ammonium sulfate, ammonium nitrate, and sodium chloride), organic chemicals, soot, metals, soil or dust particles, and biological materials (e.g., pollen and mold spores).

The air we breathe, both indoors and outdoors, always contains particle pollution. Because of their small size, particles can easily penetrate homes and buildings, increasing indoor particle concentrations. During a wildfire or other combustion-related activities, concentrations of particles can substantially increase in the air to the point that particle pollution is visible to the naked eye.

Figure 1. Fine, inhalable particulate matter (PM2.5) is the air pollutant of greatest concern to public health from wildfire smoke because it can travel deep into the lungs and may even enter the bloodstream.

Figure 1. Fine, inhalable particulate matter (PM2.5) is the air pollutant of greatest concern to public health from wildfire smoke because it can travel deep into the lungs and may even enter the bloodstream.Individuals at greater risk of health effects from wildfire smoke include those with cardiovascular or respiratory disease, older adults, children under 18 years of age, pregnant women, outdoor workers, and those of lower socio-economic status. Your patients who are at risk for health effects due to wildfire smoke should be concerned about particles that are 10 micrometers (µm) in diameter or smaller because these are the particles that generally pass through the nose and throat and enter the lungs, with the smallest particles (< 2.5 µm) possibly even translocating into circulation. Once inhaled, these particles can affect the lungs and heart and cause serious health effects. Larger particles (> 10 µm in diameter) are generally of less concern because they usually do not enter the lungs; however, they can still irritate the eyes, nose, and throat.

Particles in the air are characterized by aerodynamic diameter, and can be grouped into two main categories:

- Coarse particles (also known as PM10-2.5):particles with diameters generally larger than 2.5 µm and smaller than or equal to 10 µm. Coarse particles are primarily generated from mechanical operations (e.g., construction and agriculture), but a small percentage is present in wildfire smoke (Vicente et al. 2013; Groβ et al. 2013).

- Fine particles (also known as PM2.5): particles generally 2.5 µm in diameter or smaller represent a main pollutant emitted from wildfire smoke, comprising approximately 90% of total particle mass (Vicente et al. 2013; Groβ et al. 2013). Fine particles from wildfire smoke are of greatest health concern. This group of particles also includes ultrafine particles, which are generally classified as having diameters less than 0.1 µm.

Linking Health Effects to Exposure

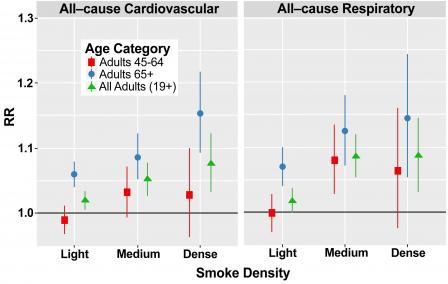

A growing body of scientific evidence links wildfire smoke exposure to various health effects (e.g., Rappold et al. 2011, Liu et al. 2015, Adetona et al. 2016, Reid et al. 2016, Wettstein et al. 2018). As shown in Figure 2, there is evidence of an increase in the risk of both cardiovascular- and respiratory-related effects in response to wildfire smoke exposure, particularly as the intensity of wildfire smoke increases.

Figure 2. Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals for emergency department visits for all cardiovascular and respiratory outcomes relative to smoke free days, at lag 0 days, stratified by age. Source: Adapted from Wettstein et. al. (2018).

Figure 2. Relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals for emergency department visits for all cardiovascular and respiratory outcomes relative to smoke free days, at lag 0 days, stratified by age. Source: Adapted from Wettstein et. al. (2018).

Because particle pollution is the main component of wildfire smoke, most of the scientific community’s understanding of the potential health consequences of wildfire smoke exposure is derived from the decades of research examining particle pollution in ambient air primarily in urban settings (e.g., U.S. EPA, 2009).

Additionally, the focus on ambient particle pollution in conveying the potential health effects attributed to wildfire smoke exposure is partly a reflection of the relatively short duration of wildfire events (i.e., days to weeks) and the relatively small number of health events (e.g., daily hospital admissions over a few weeks) observed during a wildfire event, compared to the years of data (e.g., daily hospital admissions over multiple years) available to examine the relationship between ambient air pollution and health. As a result, the information described in this course on the health effects of wildfire smoke exposure is rooted in the vast scientific evidence demonstrating a relationship between exposure to fine particle pollution and various health effects.

In addition to being defined by size fraction (e.g., PM2.5, PM10-2.5), particle pollution can also be defined by its chemical composition or the sources from which it is emitted. Research efforts have attempted to identify whether health effects are more consistently attributed to particle pollution from individual components or specific sources. Evaluation of this evidence found that many components and sources have been linked with health effects, but it remains unclear if specific individual components or sources are more closely related to specific health outcomes (U.S. EPA, 2009). More recent epidemiologic evidence focusing on particle pollution, specifically from wildfire smoke, further supports this conclusion by demonstrating similar health effects for fine particles attributed to wildfire smoke (i.e., smoke days) compared to fine particles generated from all other sources (i.e., non-smoke days) (DeFlorio-Barker et al. 2019).