Particle Pollution and Cardiovascular Effects

On this page:

- Why is particle pollution a cardiovascular health concern?

- How does particle pollution affect the cardiovascular system?

- What are the cardiovascular effects?

- What are the acute exposure effects?

- What are the chronic exposure effects?

Why is particle pollution a cardiovascular health concern?

Cardiovascular disease accounts for the greatest number of deaths in the United States. One in three Americans has heart or blood vessel disease. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), one in every three deaths is attributed to cardiovascular disease, and expenses related to cardiovascular disease represent 17 percent of overall national health expenditures (Heidenreich et al., 2011).

Traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as male gender, age, increased blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking account for about 50 percent of cardiac events. Other factors acting independently, or together with established risk factors, likely contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease. Air pollution exposure is one such risk factor and is known to exacerbate existing, and contribute to the development of, cardiovascular disease.

Evidence linking ambient particle pollution exposure and adverse effects on cardiovascular disease is particularly strong (Newby et al., 2014). The AHA concluded both that exposure to increased concentrations of fine particle pollution over a few hours to weeks can trigger cardiovascular disease-related mortality and nonfatal events and that exposures of a few years or more to increased concentrations of fine particle pollution increases the risk of cardiovascular mortality and decreases life expectancy (Brook et al., 2010).

On an individual level, the risk of cardiovascular disease from particle pollution is smaller than the risk from many other well-established factors. At the population level, acute and chronic exposure to particle pollution can increase the numbers of cardiovascular events, including hospitalizations for serious cardiovascular events, such as coronary syndrome, arrhythmia, heart failure, and stroke, particularly in people with established heart disease.

Your patients with cardiovascular disease, including those who have angina, heart failure, particular arrhythmias, or that have risk factors for heart disease (e.g., those who are smokers, obese, or older adults) may be at greater risk of having an adverse cardiovascular event from exposure to fine particles. Unlike some risk factors that contribute to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, people can take steps to reduce their exposure to particle pollution. Ninety-two percent of patients with cardiovascular disease are not informed of health risks related to air pollution (Nowka et al., 2011). Reducing population exposure to fine particle pollution has been shown to be associated with decreases in cardiovascular mortality (even within a few years of reduced exposure) (Pope et al., 2009; Correia et al., 2013).

How does particle pollution affect the cardiovascular system?

The mechanisms by which exposure to fine particle pollution can affect the cardiovascular system are under continuous examination. Exposure to inhaled fine particles appears to affect cardiovascular health through three primary pathways:

- Systemic inflammation.

- Translocation into the blood.

- Direct and indirect effects on the autonomic nervous system.

Oxidative stress is an underlying effect due to particle exposure that has been shown to impact endothelial function, pro-thrombotic processes, cardiac electrophysiology, and lipid metabolism.

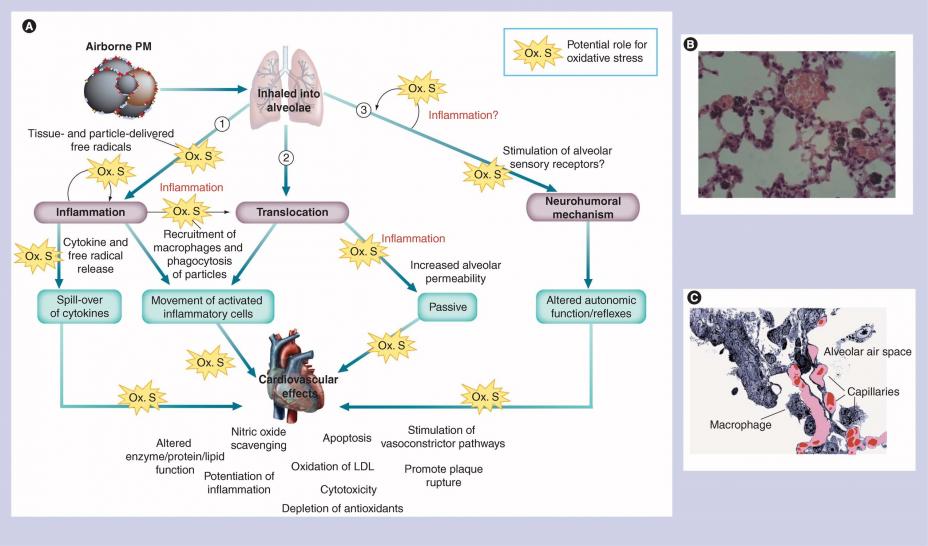

The pathways by which inhaled particle pollution affects cardiovascular health are detailed in Figure 6. Inhaled particle pollution reaches the alveoli, at which point it can increase the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and initiate an inflammatory response. Alveolar macrophages are likely to release pro-inflammatory cytokines with secondary effects on vascular control, heart rate variability, contractility, and rhythm. Alternatively, following deposition, small amounts (<1% ) of ultrafine insoluble particles, or more soluble components of any size particles (e.g., metals), may translocate from the lung directly into the circulation where the particle might have direct impact on cardiovascular function and/or have direct effects on the central nervous system with secondary effects on the heart and blood vessels via the autonomic nervous system. Figure 6. Three possible mechanisms accounting for cardiovascular effects associated with particle pollution exposure. (1) Particles induce an inflammatory response in the lungs, leading to release of cytokines and other mediators that ‘spill-over’ into the systemic circulation. (2) Some ultrafine particles can translocate from the alveolus into the circulation and then interact directly with the heart and vasculature with or without the participation of inflammatory cells. (3) Particles might activate pulmonary sensory receptors and modulate the autonomic nervous system. Oxidative stress could play a role in exacerbating the stages of each pathway, as well as promoting interactions between pathways (e.g., in conjunction with inflammation). Reprinted with permission from Future Medicine Ltd. (Miller MR, Shaw CA, Langrish JP. 2012. From particles to patients: oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Future Cardiology 8(4):577-602).

Figure 6. Three possible mechanisms accounting for cardiovascular effects associated with particle pollution exposure. (1) Particles induce an inflammatory response in the lungs, leading to release of cytokines and other mediators that ‘spill-over’ into the systemic circulation. (2) Some ultrafine particles can translocate from the alveolus into the circulation and then interact directly with the heart and vasculature with or without the participation of inflammatory cells. (3) Particles might activate pulmonary sensory receptors and modulate the autonomic nervous system. Oxidative stress could play a role in exacerbating the stages of each pathway, as well as promoting interactions between pathways (e.g., in conjunction with inflammation). Reprinted with permission from Future Medicine Ltd. (Miller MR, Shaw CA, Langrish JP. 2012. From particles to patients: oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Future Cardiology 8(4):577-602).

Several studies identify an increase in inflammatory mediators and endothelial activation biomarkers after ambient particle pollution and urban air pollution exposure (i.e., C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-alpha, prostaglandin E2, CRP, interleukin-1b, and endothelin-1) (Pope et al., 2004; Calderón-Garcidueñas et al., 2008). Traffic-related particle pollution, which consists of a mixture of pollutants, has been shown to be positively associated with a number of subclinical effects including inflammation, oxidative stress, and autonomic nervous system balance, providing evidence that traffic-related air pollution is an important source of particle pollution (Chuang et al., 2007).

Studies using concentrated air particles provide important insights into the effects of exposure to particle pollution on cardiovascular endpoints in healthy adults. Ghio and colleagues studied the effects of either filtered air or particles concentrated from the immediate environment (averaging 120 µg/m3). After two hours of exposure, subjects underwent bronchoscopy and assessment of evidence of systemic inflammation. Exposure to fine particles produced no cardiopulmonary symptoms, yet bronchoalveolar lavage showed a mild increase in neutrophils in both the bronchial and alveolar fractions, and fibrinogen was increased the next day (Ghio et al., 2000).

What are the cardiovascular effects?

Acute and chronic exposure to fine particle pollution has been shown to increase the risk of hospitalizations for cardiovascular conditions and mortality. However, multi-city epidemiologic studies of mortality and hospital admissions have provided evidence of regional heterogeneity in risk estimates (Dominici et al., 2006; Zanobetti and Schwartz, 2009). It has often been hypothesized that the regional heterogeneity observed in epidemiologic studies may be a reflection of a number of factors including different sources and the chemical composition of fine particles varying between cities and regions, as well as demographic or exposure differences. To date, the underlying factors that contribute to this heterogeneity have yet to be identified.

Clinically important cardiovascular effects of inhaled particles include:

- Acute coronary syndrome, including myocardial infarction, unstable angina.

- Arrhythmia.

- Exacerbation of chronic heart failure.

- Stroke.

- Sudden cardiac death.

Such effects can be measured after acute exposure, and there is accumulating evidence that chronic exposure accelerates atherosclerosis and reduces life expectancy.

What are the acute exposure effects?

Population-based studies, small repeated-measure panel studies, and acute exposure studies in humans support the conclusion that inhalation of particle pollution induces small changes in blood pressure, oxygen saturation, endothelial function, systemic changes in acute phase reactants, coagulation factors, inflammatory mediators, and measures of oxidative stress. Systemic blood pressure and endothelial function changes, acute coronary syndrome (including myocardial infarction and unstable angina), increased ventricular arrhythmias in people with implantable (or internal) cardiac defibrillators (ICDs), exacerbation of heart failure, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular mortality are all well-established clinical cardiovascular health effects associated with acute exposure to fine particles.

Blood pressure and endothelial function: Acute fine particle exposure causes a small increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Liang et al. 2014). Some studies of persons without cardiovascular disease indicate a small increase in blood pressure associated with acute exposures to particle pollution (Auchincloss et al., 2008; Gong et al., 2003). Increased sympathetic tone and changes in vasomotor regulation caused by inflammation and oxidative stress are the most likely physiological changes to explain an increase in blood pressure (Brook et al., 2002). Because particle pollution is ubiquitous in the ambient air, exposures resulting in increases in blood pressure at the population level can have important public health implications (Brook, 2005).

Several studies indicate that filtering particles from the air either prevents or decreases particle-induced changes in physiological and biochemical determinants of heart and vascular health (Bräuner et al., 2008; Langrish et al., 2012). However, the clinical benefit of particle filters is not yet established.

Acute coronary syndrome: Several studies indicate that the onset of unstable angina and myocardial infarction are associated with exposure to ambient fine particle pollution (Pekkanen et al. 2002; Peters et al., 2001). Clinical studies show that particle pollution exposure increases the magnitude of ST-segment changes during ischemia, suggesting that exposure to particle pollution increases the severity of ischemia (Pekkanen et al., 2002).

Arrhythmias: An increase in ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias in persons with ICDs (indicated by an increase in the discharge of the ICD) has been positively associated with increases in fine particle concentrations, which is supported by evidence of a linear exposure response (Peters et al., 2000; Rich et al., 2005; Dockery et al., 2005; Link et al., 2013). Stronger associations were found between air pollution and ventricular arrhythmias for episodes within a few days of a previous arrhythmia, suggesting that arrhythmias were triggered by air pollution episodes in combination with other factors that increased the patient’s susceptibility to arrhythmia.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common clinically important arrhythmia in older persons and imposes both a large societal burden and economic burden on the health-care system because of decreased quality of life, functional status, and hospitalizations for rhythm management, heart failure, and stroke (Rich et al., 2006).

While an increase in premature supraventricular beats is associated with long-term exposure to fine particle pollution (O'Neal et al., 2017a) and an increase in premature ventricular beats is associated with both short- and long-term exposure to increased concentrations of particle pollution (O'Neal et al., 2017b), the relationship between atrial fibrillation and exposure to particle pollution is less well established. Yet, a recent meta-analysis (Shao et al., 2016) showed an association between short-term exposure to fine particle pollution and the development of atrial fibrillation. The meta-analysis included some individuals with advanced heart disease managed with internal cardiac defibrillators (Link et al., 2013), and the positive association was not limited to fine particle pollution. Atrial fibrillation was also associated with increases in CO, NO and SO2.

Heart Failure: Several epidemiological studies indicate that acute exposures to fine particles contribute to hospitalization and mortality attributed to heart failure (Shah et al., 2013). For example, one large multi-city study conducted in 204 U.S. urban counties examined the association between daily changes in fine particle pollution concentrations and cardiovascular-related hospital admissions. The study reported that the largest association for hospital admissions is due to heart failure (Dominici et al., 2006). The authors reported a 1.28 percent increase in heart failure hospital admissions for a 10 µg/m3 increase in 24-hour average fine particle concentrations.

Stroke: Some studies have reported evidence of an increase in hospitalizations for stroke due to increases in the concentration of ambient fine particles (Wellenius et al., 2012). Recent meta-analyses have provided additional evidence supporting a relationship between both acute and chronic exposures to fine particles and various types of stroke (Shin et al., 2014; Shah et al., 2015). The mechanism for the increase in strokes is not known, but one study found a relatively small but independent effect of higher air temperature, dry air, upper respiratory tract infections, grass pollen, SO2, and suspended particles (Low et al., 2006).

Plaque stability and thrombus formation: Modulation of plaque stability and thrombus formation associated with fine particle exposure is suggested by epidemiological data indicating that the risk of unstable angina and myocardial infarction may increase by as much as 4.5 percent for each 10 µg/m3 increase in 24-hour average fine particle concentrations (Pope et al., 2006).

What are the chronic exposure effects?

There is accumulating evidence that risk from chronic exposure (months to years) to inhaled fine particles accelerates atherosclerosis and reduces life expectancy.

Atherosclerosis: Several epidemiology studies, including the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Air Pollution Study (MESA-Air), show that chronic air pollution exposure promotes atherosclerosis. This is indicated by the positive association between chronic particle exposure and an increase in coronary artery calcium (Kaufman et al., 2016), the severity of coronary artery disease (McGuinn et al., 2016), and increased thickness of the internal carotid artery (Künzli et al., 2005; Adar et al., 2013). Animal studies (Suwa et al., 2002, Araujo et al., 2008) have provided insights into the possible mechanisms that include inhibition of the anti-inflammatory capacity of plasma high-density lipoprotein, as well as increases in systemic oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, total amount of lipids in aortic lesions, and plaque turnover and extracellular lipid pools in coronary artery and aortic lesions.

Cardiovascular disease mortality: Fine particle pollution exposure is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease mortality via mechanisms that likely include pulmonary and systemic inflammation, accelerated atherosclerosis, and altered cardiac autonomic function (Dockery et al., 1993). The mechanisms of death associated with exposure to acute and chronic particle pollution are not fully known; however, prothrombotic effects precipitating myocardial infarction and stroke, autonomic instability precipitating arrhythmia, and increased oxidative stress worsening heart failure are speculated to account for the increased risk. Chronic exposure to particle pollution is most strongly associated with mortality attributable to ischemic heart disease, arrhythmia, heart failure and cardiac arrest (Pope et al., 2004).

Several seminal large cohort studies support the association of chronic exposure to air pollution and mortality. The Harvard Six Cities Study (Dockery et al., 1993) and American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention II Study (Pope et al., 2002) both show an association between chronic exposure to ambient air pollution, particularly fine particle pollution, and an increased risk of death.

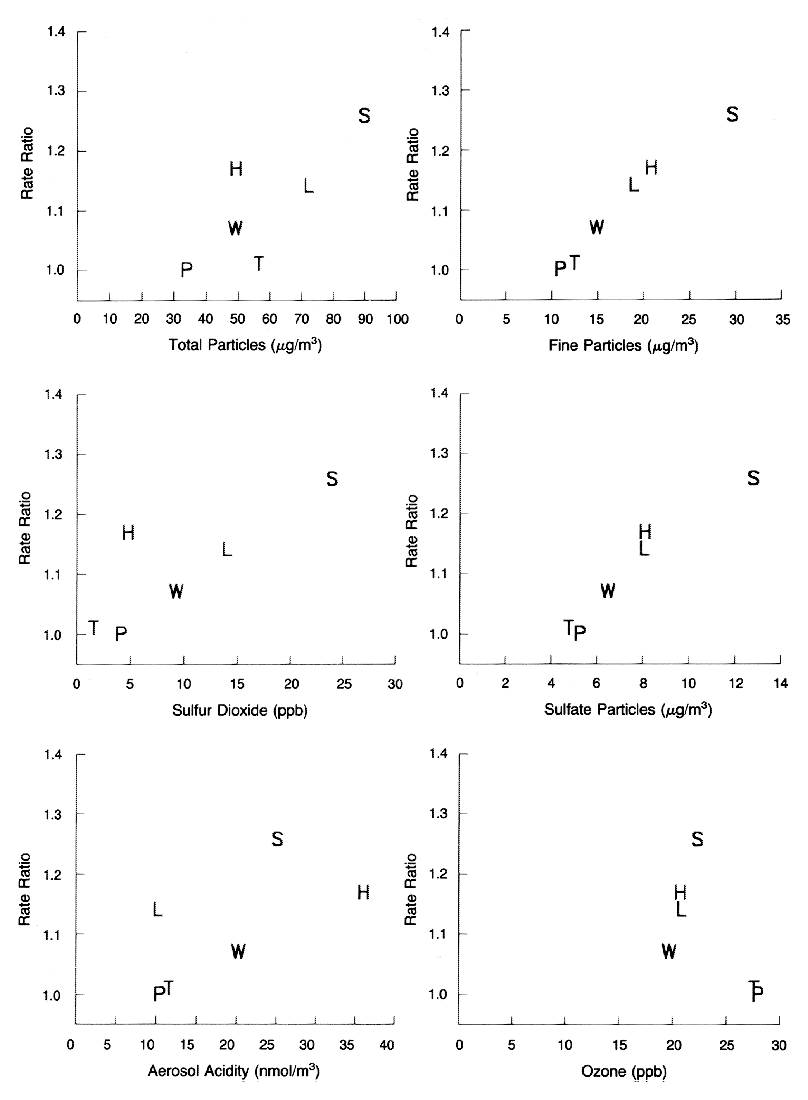

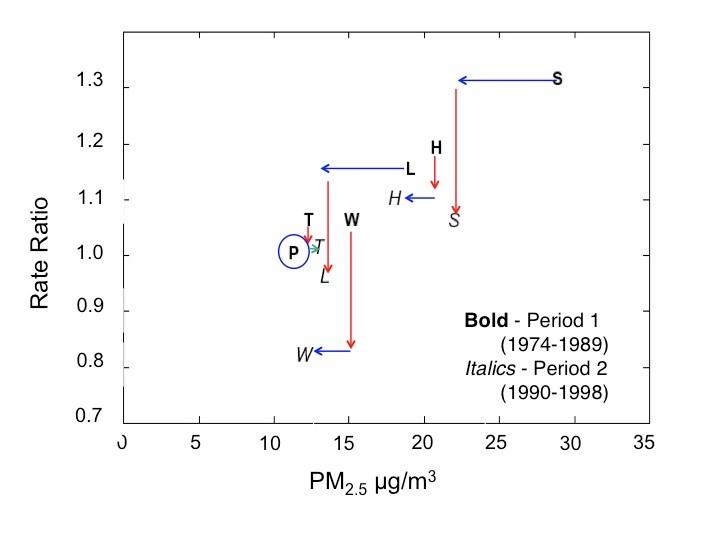

The Harvard Six Cities Study found statistically significant associations between chronic exposure to air pollution and mortality (Figure 7), specifically for fine particles and other pollutants strongly correlated with fine particles. Air pollution was also positively associated with cardiopulmonary disease deaths. A follow-up study (Laden et al., 2006) assessing risk of death after considerable improvement in air quality in these six cities showed that the risk of mortality diminished in proportion to the reduction in air pollution. As shown in Figure 8, the mortality rate ratio decreased in each city as air quality improved.

Figure 7. Estimated adjusted mortality-rate ratios and pollution levels in the Six Cities. Mean values are shown for the measures of air pollution. P denotes Portage, Wisconsin; T Topeka, Kansas; W Watertown, Massachusetts; L St. Louis, Missouri; H Harriman, Tennessee; and S Steubenville, Ohio. Mortality-rate was associated with fine particle pollutants and other co-pollutants strongly correlated to fine particle pollutants. From New England Journal of Medicine, Dockery DW, Pope CA III, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, Ferris BG Jr, Speizer Fe. 1993. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. 329(24): 1753-1759. Copyright © Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 7. Estimated adjusted mortality-rate ratios and pollution levels in the Six Cities. Mean values are shown for the measures of air pollution. P denotes Portage, Wisconsin; T Topeka, Kansas; W Watertown, Massachusetts; L St. Louis, Missouri; H Harriman, Tennessee; and S Steubenville, Ohio. Mortality-rate was associated with fine particle pollutants and other co-pollutants strongly correlated to fine particle pollutants. From New England Journal of Medicine, Dockery DW, Pope CA III, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, Ferris BG Jr, Speizer Fe. 1993. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. 329(24): 1753-1759. Copyright © Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Figure 8. Estimated adjusted rate ratios for total mortality and particle pollutant levels in the Six Cities Study by period. P denotes Portage, WI (reference for both periods); T = Topeka, KS; W = Watertown, MA; L = St. Louis, MO; H = Harriman, TN; S = Steubenville, OH. A term for Period 1 (1 if Period 2, 0 if Period 1) was included in the model. Bold letters represent Period 1 (1974–1989) and italicized letters represent Period 2 (1990–1998). In Period 1, fine particle pollution (µg/m3) is defined as the mean concentration during 1980–1985, the years where there are monitoring data for all cities (18). In Period 2, fine particle pollution is defined as the mean concentrations of the estimated fine particle pollution in 1990–1998. Blue arrows represent interval changes in annual fine particle pollution concentrations, and Red arrows represent changes in adjusted rate rations for total morality. (Laden F, Schwartz J, Speizer FE, Dockery DW. 2006. Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality: extended follow-up of the Harvard Six Cities study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173 (6):667-672.) Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2016 American Thoracic Society. The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society.

Figure 8. Estimated adjusted rate ratios for total mortality and particle pollutant levels in the Six Cities Study by period. P denotes Portage, WI (reference for both periods); T = Topeka, KS; W = Watertown, MA; L = St. Louis, MO; H = Harriman, TN; S = Steubenville, OH. A term for Period 1 (1 if Period 2, 0 if Period 1) was included in the model. Bold letters represent Period 1 (1974–1989) and italicized letters represent Period 2 (1990–1998). In Period 1, fine particle pollution (µg/m3) is defined as the mean concentration during 1980–1985, the years where there are monitoring data for all cities (18). In Period 2, fine particle pollution is defined as the mean concentrations of the estimated fine particle pollution in 1990–1998. Blue arrows represent interval changes in annual fine particle pollution concentrations, and Red arrows represent changes in adjusted rate rations for total morality. (Laden F, Schwartz J, Speizer FE, Dockery DW. 2006. Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality: extended follow-up of the Harvard Six Cities study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173 (6):667-672.) Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2016 American Thoracic Society. The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society.

The American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention II Study also assessed the relationship between chronic exposure to fine particle pollution and mortality, but on a national scale (Pope et al., 2002). Similar to the Harvard Six Cities study, the ACS study reported evidence of a positive association between both all-cause and cardiopulmonary mortality and chronic exposure to fine particles.

In contrast to previous studies focusing on mortality in the entire population, Miller and colleagues examined the association between chronic exposure to fine particle pollution and clinical cardiovascular events in post-menopausal women without previous cardiovascular disease (Miller et al., 2007). In this study, one or more fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular event(s) occurred which included death from coronary heart disease or cerebrovascular disease, coronary revascularization, myocardial infarction, and stroke. The authors observed a marked increase in the risk of both cardiovascular events (24% increase), cerebrovascular events (35% increase), and cardiovascular-related mortality (76% increase) in this cohort of women for each 10 µg/m3 increase in the annual average concentration of fine particles.