What is Particle Pollution?

On this page:

- What is particle pollution and what types of particles are a health concern?

- Where does particle pollution come from?

- Where and when is particle pollution a problem?

What is particle pollution and what types of particles are a health concern?

Particle pollution, also known as particulate matter or PM, is a general term for a mixture of solid and liquid droplets suspended in the air. Particle pollution comes in many sizes and shapes and can be made up of a number of different components, including acids (such as sulfuric acid), inorganic compounds (such as ammonium sulfate, ammonium nitrate, and sodium chloride), organic chemicals, soot, metals, soil or dust particles, and biological materials (such as pollen and mold spores).

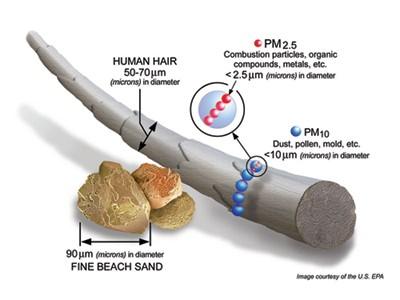

The air we breathe indoors and outdoors always contains particle pollution. Some particles, such as dust, dirt, soot, or smoke, are large enough to be seen with the naked eye. Others are so small they can only be detected using an electron microscope (Figure 1).

Particles that are 10 micrometers (µm) in diameter or smaller pose the greatest problems. These smaller particles generally pass through the nose and throat and enter the lungs. Once inhaled, these particles can affect the lungs and heart and cause serious health effects in individuals at greatest risk, such as people with heart or lung disease, people with diabetes, older adults and children (up to 18 years of age). Larger particles (> 10 µm) are generally of less concern because they usually do not enter the lungs, although they can still irritate the eyes, nose, and throat.

Particles of concern can be grouped into two main categories:

- Coarse particles (also known as PM10-2.5): particles with diameters generally larger than 2.5 µm and smaller than, or equal to, 10 µm in diameter. Note that the term large coarse particles in this course refers to particles greater than 10 µm in diameter.

- Fine particles (also known as PM2.5): particles generally 2.5 µm in diameter or smaller. This group of particles also encompasses ultrafine and nanoparticles which are generally classified as having diameters less than 0.1 µm.

Note that PM10 is a term that encompasses coarse, fine and ultrafine particle fractions.

Fine and coarse particles differ by their sources, composition, dosimetry (deposition and retention in the respiratory system), and health effects as observed in scientific studies. Though it is often hypothesized that specific components or sources may be responsible for particle pollution-related mortality and morbidity, the available evidence is not sufficient to allow differentiation of those components or sources that are more closely related to specific health outcomes. Rather, the overall evidence indicates that many particle pollution components can be linked with such effects. This course will mainly focus on the health effects of fine particles because the scientific evidence of health effects is much stronger than for other size fractions.

Where does particle pollution come from?

Some particles, known as primary particles, are emitted directly from a source, such as construction sites, unpaved roads, smokestacks or fires. Other particles, known as secondary particles, form in complicated atmospheric reactions involving chemicals such as sulfur dioxides and nitrogen oxides that are emitted from power plants, industries and automobiles. Secondary particles make up most of the fine particle pollution in the United States.

Cooking, smoking, dusting, and vacuuming can also produce particle pollution, particularly in indoor settings. Particles produced by combustion are more likely to be fine particles, while particles of crustal (earth) and biological origin are more likely to be coarse particles.

Where and when is particle pollution a problem?

Particle pollution is found everywhere - not just in haze, smoke, and dust, but also in air that looks clean. Particle pollution can occur year-round and presents air quality problems at concentrations found in many major cities throughout the United States.

Some particles can remain in the atmosphere for days to weeks. Consequently, particle pollution generated in one area can travel hundreds or thousands of miles and influence the air quality of regions far from the original source.

Particle pollution levels can be especially high in the following circumstances:

- Near busy roads, in urban areas (especially during rush hour), and in industrial areas.

- When there is smoke in the air from wood stoves, fireplaces, campfires, or wildfires.

- When the weather is calm, allowing air pollution to build up. For example, hot humid days with stagnant air have much higher particle concentrations than days with air partially “scrubbed” by rain or snow.

Because of their small size, fine particles outdoors can penetrate into homes and buildings. Therefore, high outdoor particle pollution levels can elevate indoor particle pollution concentrations.

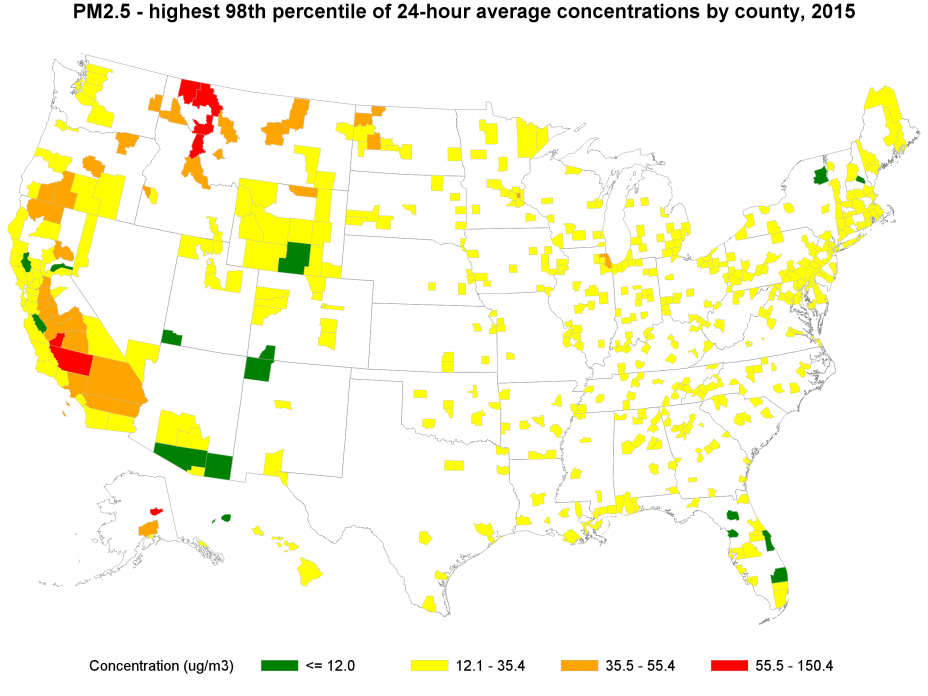

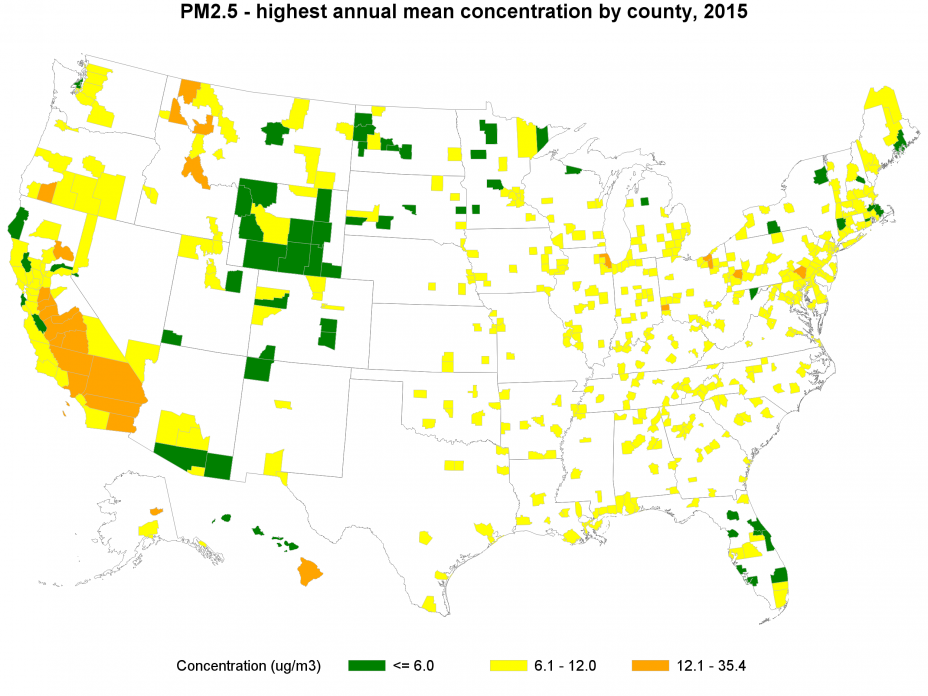

Based on 2015 data, Figure 2 and 3 show how likely it may be for a particular area to experience air quality advisories for fine particle pollution based on short-term (Figure 2) and annual (Figure 3) averaging.

Figure 2. U.S counties with high 24-hour average particle pollution concentrations in 2015. This map depicts fine particle pollution concentrations by U.S. county for 2015 based on short-term (24-hour) average concentrations. The map’s color key is based on categories of the Air Quality Index (AQI) (see Patient Exposure and the Air Quality Index). All orange and red areas exceeded the 24-hour ambient air quality standards for fine particle pollution during 2015. The map illustrates how likely it may be for a particular area to experience air quality advisories for particle pollution based on short-term averaging.

Figure 2. U.S counties with high 24-hour average particle pollution concentrations in 2015. This map depicts fine particle pollution concentrations by U.S. county for 2015 based on short-term (24-hour) average concentrations. The map’s color key is based on categories of the Air Quality Index (AQI) (see Patient Exposure and the Air Quality Index). All orange and red areas exceeded the 24-hour ambient air quality standards for fine particle pollution during 2015. The map illustrates how likely it may be for a particular area to experience air quality advisories for particle pollution based on short-term averaging. Figure 3. U.S counties with high annual mean particle pollution concentrations in 2015. This map depicts fine particle pollution concentrations by U.S. county for 2015 based on long-term (annual) average concentrations. The map’s color key is based on categories of the Air Quality Index (AQI) (see Patient Exposure and the Air Quality Index). All orange and red areas exceeded the annual ambient air quality standards for fine particle pollution during 2015. The map illustrates how likely it may be for a particular area to experience air quality advisories for particle pollution based on annual averaging.

Figure 3. U.S counties with high annual mean particle pollution concentrations in 2015. This map depicts fine particle pollution concentrations by U.S. county for 2015 based on long-term (annual) average concentrations. The map’s color key is based on categories of the Air Quality Index (AQI) (see Patient Exposure and the Air Quality Index). All orange and red areas exceeded the annual ambient air quality standards for fine particle pollution during 2015. The map illustrates how likely it may be for a particular area to experience air quality advisories for particle pollution based on annual averaging.

Fine particle pollution often has a seasonal pattern. Fine particle concentrations in the eastern half of the United States are typically higher from July through September, when sulfates are more readily formed from sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions from power plants in that region and contribute to the formation of fine particles.

Fine particle concentrations tend to be higher from October through December in many areas of the West, in part because fine particle nitrates are more readily formed in cooler weather and due to wood stove and fireplace use.

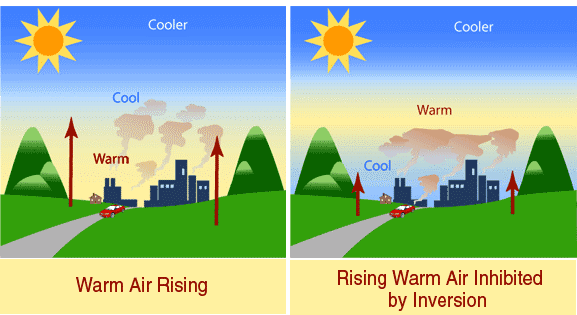

In some locations, such as mountainous areas where wood is burned for heat, particle pollution levels can be especially high during wintertime inversions (Figure 4). An inversion traps the smoke close to the ground, allowing particle pollution levels to increase before the inversion lifts.

Figure 4. Inversions. Sometimes a layer of cooler air is trapped near the ground by a layer of warmer air above. This is called an inversion and can last all day, or even for several days. When the air cannot rise, pollution at the surface also is trapped and can accumulate, leading to higher concentrations of ozone and particle pollution. A variety of conditions can cause inversions to form. The most common is a nighttime inversion, in which clear skies allow air at the surface to cool faster than the air above.

Figure 4. Inversions. Sometimes a layer of cooler air is trapped near the ground by a layer of warmer air above. This is called an inversion and can last all day, or even for several days. When the air cannot rise, pollution at the surface also is trapped and can accumulate, leading to higher concentrations of ozone and particle pollution. A variety of conditions can cause inversions to form. The most common is a nighttime inversion, in which clear skies allow air at the surface to cool faster than the air above.

This situation is exacerbated by complex terrain. Inversions are more likely to occur in valleys where pollution is trapped both vertically (by the warmer air above) and horizontally (by the valley walls).

To find out more about particle pollution patterns in your area, visit EPA's AirData website.