Particle Pollution Exposure

On this page:

- Why is particle pollution exposure a health concern?

- What groups are at increased risk from particle pollution?

- Are there symptoms of particle pollution exposure?

- How does an individual's genetic background influence particle pollution response?

- How are particles deposited in the respiratory system?

- What are the lung’s defense mechanisms against fine particles?

Why is particle pollution exposure a health concern?

Both acute and chronic particle pollution exposures have been linked with health problems. An extensive body of scientific evidence shows that exposure to fine particles can cause cardiovascular effects, including heart attacks, heart failure, and strokes, which results in hospital admissions, emergency department visits, and, in some cases, premature death. The scientific evidence shows exposure to fine particles is also likely to cause respiratory effects, including asthma attacks resulting in hospital admissions and emergency department visits, reduced lung development in children, and increased respiratory symptoms such as coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath. There is more limited scientific evidence for a broader range of health effects associated with fine particle exposure (e.g., developmental and reproductive effects, cancer) (U.S. EPA, 2009).

Although the overall level of confidence in the exposure-health effect relationship varies across the health effects examined, epidemiologic studies have shown that the association between particle pollution and morbidity and mortality is not limited to acute effects on high air pollution days, but can also result from chronic exposures to particle pollution. This has been further demonstrated in both acute and chronic exposure studies that depict a clear concentration-response relationship over a wide range of particle pollution concentrations, including those particle pollution concentrations observed during a typical day.

What groups are at increased risk from particle pollution?

Although not all groups of people respond to air pollution exposure in the same way, exposure to particle pollution can elicit a range of health effects across populations. Sensitive groups, also called at-risk populations, are at increased risk for experiencing adverse air pollution-related health effects. These groups can be at increased risk due to intrinsic (biological) factors, extrinsic (external, non-biological) factors, higher exposure, and/or increased dose at a given concentration (U.S. EPA, 2013). The severity of the health effects that these groups experience may be much greater than in the general population.

Evidence for the factors that increase risk from particle pollution comes from animal toxicology, controlled human studies, and epidemiological studies (U.S. EPA, 2009). Sensitive groups considered to be at increased risk of particle pollution-related health effects include: people with heart or lung disease, children (less than 18), older adults![]() older adults In many studies, older adults are defined as ages 65 years and older due to age definitions provided in health datasets such as the Medicare database. In terms of increased risk from air pollution, there is not a specific age at which someone is considered “older” because people age at different rates. As a person ages, there is greater susceptibility to environmental hazards due to a number of factors, including higher prevalence of pre-existing respiratory and cardiovascular disease, as well as the gradual decline in physiological defenses that occur as part of the aging process. , people with diabetes, and people of lower SES

older adults In many studies, older adults are defined as ages 65 years and older due to age definitions provided in health datasets such as the Medicare database. In terms of increased risk from air pollution, there is not a specific age at which someone is considered “older” because people age at different rates. As a person ages, there is greater susceptibility to environmental hazards due to a number of factors, including higher prevalence of pre-existing respiratory and cardiovascular disease, as well as the gradual decline in physiological defenses that occur as part of the aging process. , people with diabetes, and people of lower SES![]() lower socio-econonmic status (SES) A composite measure that is often comprised of a number of indicators, including economic status measured by income, social status measured by education, and work status measured by occupation. Each of these linked factors can influence a population's susceptibility to particle pollution-related health effects (Dutton and Levine, 1989).. Although the evidence is less clear with respect to particle pollution-related health effects on pregnant women and the developing fetus, during high particle events, such as a smoke episode, it is worth recommending measures that can reduce particle exposures.

lower socio-econonmic status (SES) A composite measure that is often comprised of a number of indicators, including economic status measured by income, social status measured by education, and work status measured by occupation. Each of these linked factors can influence a population's susceptibility to particle pollution-related health effects (Dutton and Levine, 1989).. Although the evidence is less clear with respect to particle pollution-related health effects on pregnant women and the developing fetus, during high particle events, such as a smoke episode, it is worth recommending measures that can reduce particle exposures.

Evidence about effects in people with heart or lung disease is discussed in detail in the Cardiovascular Effects and Respiratory Effects sections of the course. The other sensitive groups are discussed below.

Life stages that are often examined to assess whether there is evidence of increased risk include:

- Childhood (less than 18 years of age).

- Older adulthood (65 years of age and older).

Increased risk in children is related to the following factors:

- Children spend more time outdoors at greater activity levels than adults, resulting in higher exposures and higher doses of ambient particle pollution per body weight and lung surface area.

- Children are more likely to have asthma than adults.

- Children’s developing lungs are prone to damage, including irreversible effects through adolescence.

Increased risk in older adults is related to the higher prevalence of pre-existing respiratory or cardiovascular diseases found in this age group, as well as the gradual decline in physiological defenses that occur as part of the aging process.

Adults with diabetes may experience chronic inflammation, which may increase their sensitivity to the adverse health effects attributed to particle pollution exposure. A growing body of scientific evidence indicates that adults with diabetes experience changes in heart (e.g., heart rate variability) and vasculature function, as well as markers of inflammation in response to acute exposures to fine particles. These changes in the cardiovascular system may lead to more overt health outcomes, in some cases resulting in cardiovascular-related hospital admissions or premature mortality.

People with lower SES generally have the following factors that might increase the group's risk of particle pollution-related health effects:

- A higher prevalence of pre-existing diseases.

- Limited access to medical care.

- Increased nutritional deficiencies.

In addition, they may be exposed to higher levels of pollutants due to the location of their homes, schools, and work environments. Surrogates of SES, such as educational attainment, residential location, and nutritional status have been shown in some studies to modify the association between particle pollution and morbidity and mortality outcomes (U.S. EPA, 2009).

Epidemiological studies show that indicators of lower SES (e.g, educational attainment, household income) potentially increase the risk of particle pollution-related health effects at the population level, although it is unclear how this translates to individual-level risk. Clinicians and public health officials should be aware of the potential role of SES on the risk of particle pollution-related health effects. However, other than conveying advice about reducing exposure and planning for the management of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, there may be only minimal actions that can be done on the individual level.

Are there symptoms of particle pollution exposure?

Symptoms are not a reliable indicator of whether particle pollution is at an unhealthy level. There may be no immediate symptoms even at relatively high concentrations of exposure.

A person with respiratory disease may not be able to breathe as deeply or as vigorously as normal and may experience coughing, chest discomfort, wheezing, shortness of breath, and unusual fatigue. For a person with cardiovascular disease, exposure to unhealthy levels of particle pollution may not produce any change in respiratory symptoms yet can still cause serious problems in a short period of time, including heart attacks (Hassing, 2009).

How does an individual's genetic background influence particle pollution response?

People's response to particle pollution exposure varies considerably. Some studies have investigated the relationship between the genetic characteristics of individuals and their response to particle pollution (Schwartz et al., 2005; Chahine et al., 2007; Baccarelli et al., 2008; Park et al., 2006). Taken together, these studies implicate oxidative stress as an important pathway for the effects of particles and suggest that an individual's genetic background may influence health effects caused by both acute and chronic particle pollution exposures.

How are particles deposited in the respiratory system?

There are three primary mechanisms of particle deposition in the airways:

- Impaction -- coarse particles primarily deposit in the nasal, pharyngeal and laryngeal passages, trachea, and bronchi.

- Sedimentation -- fine particles primarily deposit in the respiratory bronchioles and alveoli.

- Diffusion -- ultrafine particles diffuse to respiratory surfaces and deposit.

Other mechanisms, such as interception, are important only with elongated particles or fibers, where an edge of the particle touches an airway passage to become deposited.

Particle transport and deposition in the airways varies depending on physiological factors, such as breathing rates, and on particle characteristics, such as size. As a result, particles may be deposited in three different regions of the respiratory system:

- Extrathoracic (nasal, pharyngeal, and laryngeal passages).

- Tracheobronchial.

- Alveolar (pulmonary).

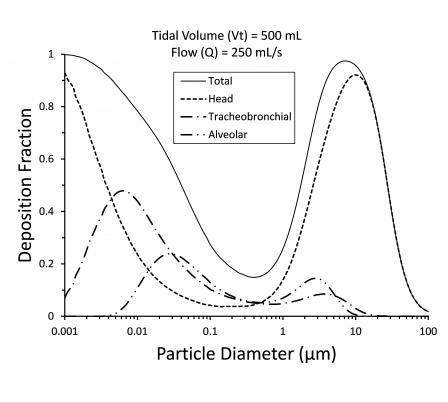

The deposition of spherical unit density (i.e., 1g/cc) particles is illustrated in Figure 5. Three key factors affect deposition: mode of breathing (i.e., mouth, nose, or oronasal), breathing pattern (i.e., tidal volume, breathing frequency), and the characteristics of particles (i.e., size, shape, mass, hygroscopicity![]() hygroscopicity The quality of absorbing or attracting moisture from the air., and solubility).

hygroscopicity The quality of absorbing or attracting moisture from the air., and solubility).

Figure 5. Mathematical model of particle deposition via nasal breathing in the whole lung (Total), nose, naso-pharynx and larynx (Head), tracheobronchial airways, and alveolar region in healthy adults. Tidal volume (Vt) is 500 mL, frequency of breathing is 15 bpm, and flow rate (Q) is 250 mL/sec. Deposition was adjusted for particle inhalability, which is why particle deposition decreases for particles greater than 10 μm. Particles in the 0.3 to 0.5 μm range show the lowest deposition for any of the regions. (Above simulation conducted using the Multiple-Path Particle Dosimetry Model v3.01, Applied Research Associates © 2015).Coarse particles (particles with diameters generally larger than 2.5 µm and smaller than, or equal to, 10 μm in diameter) that penetrate beyond the nasopharynx deposit in the large airways, primarily the tracheobronchial region. High linear velocities in the bronchi cause coarse particles to concentrate in the areas of highest impaction, the airways’ bifurcations. Prone to epithelial damage and even metaplasia, these “hot spots” also have high particle densities per tissue surface area. Additional hot spots can be created in locations with excess mucus accumulation or excess production or when there is an abnormal growth in the airways that disturbs the airflow.

Figure 5. Mathematical model of particle deposition via nasal breathing in the whole lung (Total), nose, naso-pharynx and larynx (Head), tracheobronchial airways, and alveolar region in healthy adults. Tidal volume (Vt) is 500 mL, frequency of breathing is 15 bpm, and flow rate (Q) is 250 mL/sec. Deposition was adjusted for particle inhalability, which is why particle deposition decreases for particles greater than 10 μm. Particles in the 0.3 to 0.5 μm range show the lowest deposition for any of the regions. (Above simulation conducted using the Multiple-Path Particle Dosimetry Model v3.01, Applied Research Associates © 2015).Coarse particles (particles with diameters generally larger than 2.5 µm and smaller than, or equal to, 10 μm in diameter) that penetrate beyond the nasopharynx deposit in the large airways, primarily the tracheobronchial region. High linear velocities in the bronchi cause coarse particles to concentrate in the areas of highest impaction, the airways’ bifurcations. Prone to epithelial damage and even metaplasia, these “hot spots” also have high particle densities per tissue surface area. Additional hot spots can be created in locations with excess mucus accumulation or excess production or when there is an abnormal growth in the airways that disturbs the airflow.

Deeper breathing promotes peripheral particle pollution deposition (i.e., in small airways and alveoli); fast shallow breathing favors more central deposition (i.e., in the trachea and large bronchi). During quiet breathing, most of us breathe through the nose, which acts as the first in a series of protective mechanisms. With its narrow air passages, mucosal folds, and mucous layer covering ciliated epithelial cells, the nose can effectively filter most coarse particles.

Fine particles (generally 2.5 μm in diameter or smaller) and ultrafine particles (diameters less than 0.1 µm) are primarily deposited in the small peripheral airways and the alveoli (the pulmonary region). A large proportion of fine and ultrafine particles that reach the small airways and alveoli remain suspended in the airways and are subsequently exhaled. As illustrated in Figure 5, for ultrafine particles of around 0.03 µm and less, the pattern of deposition begins shifting toward the mouth.

Higher minute ventilation (e.g., during exercise) increases particle dose and deposition by two mechanisms:

- It causes a gradual switch from nose to oronasal breathing, which reduces the nose’s role as a physiologic filter.

- It increases tidal volume and breathing rate, which increases the total volume of air (and particles) inhaled. Moreover, higher airflow carries the particles more peripherally, increasing the deposition of ultrafine particles in the alveolar region.

What are the lung’s defense mechanisms against fine particles?

Inhaled fine particle pollution deposited on the surface of the airways either may stay intact or partially or totally dissolve. Deposited fine particle pollution is cleared by two mechanisms:

- Mucociliary clearance.

- Phagocytosis.

Mucociliary clearance, the pulmonary system’s first and the most critical line of defense against fine particles, removes the vast majority of inhaled particles deposited in the tracheobronchial airways. This system receives additional support from the body’s cough, immunologic, phagocytic, and enzymatic defenses. The mucociliary escalator of the tracheobronchial airways very effectively moves particles toward the nasopharynx. There, the particle pollution-loaded mucus is swallowed or expectorated.

Under normal conditions, mucociliary transport in healthy individuals clears most insoluble particles within 24 hours of deposition. When normal clearance becomes impaired (as in the case of many chronic conditions such as smoking or with respiratory diseases like asthma and COPD), particle pollution retention increases and adverse health effects are compounded.

Phagocytosis is the primary clearance mechanism for removing any foreign material (particles, microorganisms) from the alveolar region. Phagocytes (i.e., macrophages, monocytes, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes) are present throughout the respiratory tract. Alveolar macrophages are particularly important and remove particles following phagocytosis by migration to the tracheobronchial airways or into the interstitium to reach the lymphatic system. The efficiency of phagocytosis decreases with decreasing particle size below about 1 μm, and particles can be retained in the alveolar region for multiple years.

Other mechanisms also remove fine particles from the lower respiratory tract. Some particles move from the epithelial surface into the interstitium where they may enter pulmonary lymph flow with transport to lymph nodes and subsequently reach the blood and other organs (e.g., heart or brain). In animal studies, a small fraction (<1%) of insoluble ultrafine particles deposited in the lung are rapidly translocated (<1 hour) from the alveolar region directly into the blood. These particles are transported to other organs, mainly the liver, spleen, kidneys, and to a lesser extent the heart and brain. There is extensive experimental evidence in rodents for direct translocation of insoluble particles (<0.2 µm in diameter) into the blood. However, human studies using radiolabeled particles have not identified insoluble particle translocation in organs such as the liver, although this may be due to the relatively small amount translocated into the blood. Despite these additional clearance pathways, some particles will accumulate in the lung, remaining there permanently.

The respiratory tract is not only a dominant portal of entry for airborne pollutants, but it also serves as the site of initiation for subsequent neural, cardiac, and vascular responses. Repeated, frequent exposure to particle pollution may overburden the pulmonary defense system, resulting in a more severe local and systemic response.