Health Effects of Ozone in Patients with Asthma and Other Chronic Respiratory Disease

- Introduction

- Asthma basics

- Asthma statistics

- How does ozone affect people with asthma?

- COPD and other chronic respiratory disease

Introduction

Patients with pre-existing respiratory diseases are potentially at increased risk of adverse effects of ozone exposure because the response to ozone may interact with the pathophysiology of the underlying disease or simply because these patients generally have less pulmonary reserve and cannot tolerate the reduction in lung function or the increase in symptoms.

People with asthma are a large and growing segment of the population and are also known to be especially susceptible to the effects of ozone exposure. Because the prevalence of asthma in children is particularly high and because children are generally at risk of higher exposures due to time spent in exercise and outdoors, they may be disproportionately affected by ozone exposure.

On days when ozone levels are high, people with asthma tend to experience:

- Lung function decrements

- Increased respiratory symptoms

- Increased medication usage

- Increased frequency of asthma attacks

- Increased use of health care services

Although the data are inconsistent, some epidemiological studies suggest that long-term exposure to ozone could play a role in the development of asthma. Long-term exposure of very young laboratory animals results in changes in the development of immune cells in the respiratory tract and exposure of adult animals enhances the tendency to develop sensitization to allergens.

Asthma basics

Clinically, asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways in which many cell types play a role, in particular mast cells, eosinophils, and T lymphocytes. In susceptible individuals, the inflammation causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and cough, particularly at night and/or early morning. These symptoms are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction that is at least partly reversible, either spontaneously or with treatment. The inflammation also causes an associated increase in airway responsiveness to a variety of stimuli. The basic physiologic alterations of asthma are bronchospasm, measured by reduction in obstructive (airflow-related) lung function, edema, and hypersecretion.

Evidence of bronchial inflammation is obtained from:

- Measuring nonspecific bronchial hyperresponsiveness

- Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

- Bronchial biopsies

- Induced sputum

The majority of asthma is associated with allergic responses to common airborne allergens such as household dust mites (HDM), pollens, animal dander, and molds. The disease has a definite genetic component. In genetically predisposed individuals, exposure to allergens can lead to immunologic sensitization.

Sensitization involves the production of antibodies that belong to the immunoglobulin E (IgE) class. Upon re-exposure to allergens, immediate and delayed (late-phase) responses may occur in a subpopulation of sensitized individuals. These responses include airway inflammation (characterized by the presence of inflammatory cells such as eosinophils and activated T-helper lymphocytes) and airway obstruction that is reversible either spontaneously or with appropriate medication.

Figure 10: Factors involved in induction and exacerbation of asthma. Induction of asthma may occur in genetically susceptible people upon exposure to common allergens or certain chemicals. Nonspecific irritants and promoters may facilitate induction through injury and increased uptake of allergens or by modulating immune responses (dashed arrow). Both allergens and irritants may exacerbate existing asthma.

Inflammation and airway obstruction in asthma are reversible. Consequently, severity of the disease is variable (double-headed arrows), depending on environmental influences as well as susceptibility factors as indicated here.Induction of asthma refers both to the acquisition of immunologic sensitivity to allergens and the progression to a clinically detectable disease that is indicated by reversible airway obstruction. Exacerbation of asthma may occur with subsequent re-exposure to allergens or by exposure to a number of nonspecific triggers of lung inflammation and airway obstruction, such as respiratory viruses, tobacco smoke, wood smoke, or certain air pollutants like ozone.

Figure 10: Factors involved in induction and exacerbation of asthma. Induction of asthma may occur in genetically susceptible people upon exposure to common allergens or certain chemicals. Nonspecific irritants and promoters may facilitate induction through injury and increased uptake of allergens or by modulating immune responses (dashed arrow). Both allergens and irritants may exacerbate existing asthma.

Inflammation and airway obstruction in asthma are reversible. Consequently, severity of the disease is variable (double-headed arrows), depending on environmental influences as well as susceptibility factors as indicated here.Induction of asthma refers both to the acquisition of immunologic sensitivity to allergens and the progression to a clinically detectable disease that is indicated by reversible airway obstruction. Exacerbation of asthma may occur with subsequent re-exposure to allergens or by exposure to a number of nonspecific triggers of lung inflammation and airway obstruction, such as respiratory viruses, tobacco smoke, wood smoke, or certain air pollutants like ozone.It also has been suggested that some of these triggers facilitate the induction of asthma by increasing sensitization to allergens. This may occur via modulation of immune responses or injury to airway epithelium, effects that allow allergens to penetrate the immune system barrier and to be taken up by antigen-processing cells.Induction of asthma refers both to the acquisition of immunologic sensitivity to allergens and the progression to a clinically detectable disease that is indicated by reversible airway obstruction. Exacerbation of asthma may occur with subsequent re-exposure to allergens or by exposure to a number of nonspecific triggers of lung inflammation and airway obstruction, such as respiratory viruses, tobacco smoke, wood smoke, or certain air pollutants like ozone.

Susceptibility factors that are indicative of the potential for exposure to allergens and nonallergic triggers include, in addition to the genetic component:

- Overall health status

- Lifestyle

- Socioeconomic status

- Residential location

- Overall exposure history

Asthma statistics

According to asthma statistics compiled by the American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI):

- About 23 million people, including almost 7 million children, have asthma.

- An average of 1 out of every 10 school-aged children has asthma.

- 2011 data from the Centers for Disease Control indicate an asthma prevalence rate of 8.4% in the United States.

- Asthma was responsible for 3,384 deaths in the United States in 2005.

- It is estimated that the number of people with asthma will grow by more than 100 million by 2025.

- Asthma accounts for approximately 500,000 hospitalizations each year; Asthma is the third-ranking cause of hospitalization among children under 15.

- The annual economic cost of asthma is about $20 billion. Direct costs make up about $15 billion of that total, and indirect costs such as lost productivity add another $5 billion.

Trends toward increased prevalence, deaths, and costs of the disease have also been observed in many other countries. The increase in asthma incidence cannot be reconciled simply by changes in diagnostic categorization, and it has been too rapid to be explained by alterations in the gene pool. For these reasons, there has been a growing interest in the association between the environment and asthma.

How does ozone affect people with asthma?

There are two major mechanisms by which people with asthma might be more severely affected by ozone than those without asthma. The first is that those with asthma might be more responsive or sensitive to ozone and therefore experience the lung function changes and respiratory symptoms common to all, but either at lower concentrations or with greater magnitude. There is evidence from some controlled exposure studies and some epidemiologic studies that this may be true. By far, the greater individual and public health concern is that the injury, inflammation, and increased airway reactivity induced by ozone exposure may result in a worsening of a person's underlying asthma status, increasing the probability of an asthma exacerbation or a requirement for more treatment.

Some panel studies have found relationships of ambient ozone concentration with increased asthma symptoms and with increased medication use among children with asthma. Other epidemiologic studies have documented relationships between higher ozone levels and increased ER visits and hospital admissions for asthma in the warm season. In a camp for children with asthma in New York, it was observed that on days when ozone concentrations were high, children in camp used their asthma inhalers more frequently than on days when ozone levels were low. Presumably this was due to a perception that their asthma was worse on those days. Measures of peak expiratory flow in these children were lower on days when ozone levels were high, supporting this hypothesis. Although results are somewhat inconsistent among panel studies of asthmatics, one of the largest (Mortimer 2002) with 846 asthmatic children from eight U.S. urban areas monitored during the course of a summer found evidence for lower values of peak expiratory flow and an increased prevalence of respiratory symptoms for several mornings after days when ozone levels were high. Reductions in morning lung function and an increase in morning symptoms are an indication of worsening asthma status and are consistent with increased asthma exacerbations. There is some evidence that children with more severe asthma are more likely to experience these ozone-related effects than those with mild asthma.

Figure 11: Unscheduled daily asthma medication use by children with asthma is associated with summertime ozone air pollution.

Figure 11: Unscheduled daily asthma medication use by children with asthma is associated with summertime ozone air pollution.

Use of inhaled beta-adrenergic agonist medication to alleviate asthma aggravation is plotted against ozone concentrations during summer asthma camps conducted for children 7 to 13 years old, during the last week of June, 1991 through 1993, in the Connecticut River Valley, downwind of New York City. Each child's normal physician-prescribed medications were maintained throughout each week. An increase in the 1-hour daily maximal ozone concentration from 84 to 160 ppb was significantly associated with increased unscheduled medications administered per day. Source: Thurston et al., 1997

In Atlanta, GA, in Buffalo and New York City, NY, and in many other places throughout the United States, visits to the hospital emergency room for asthma were more frequent on days when ozone concentrations were high (generally above 110 ppb as a 1-hour average or 60 ppb as a 7-hour average) compared to low ozone days. Similarly, in some places, hospital admissions for asthma were higher following days when ozone levels were elevated with effects generally being larger in the warm season than in the cold season.

Figure 12: Childhood asthma and reactive airway disease appears to be exacerbated after periods of high ozone pollution. No dose-response relationship was observed between the number of clinic visits and 1-hour maximum ozone levels under 0.11 ppm (110 ppb); however, when ozone levels equaled or exceeded 0.11 ppm, the number of visits to hospital clinics for childhood asthma or reactive airway disease on the following day was about one-third higher than at other times. Source: White et al., 1994

Figure 12: Childhood asthma and reactive airway disease appears to be exacerbated after periods of high ozone pollution. No dose-response relationship was observed between the number of clinic visits and 1-hour maximum ozone levels under 0.11 ppm (110 ppb); however, when ozone levels equaled or exceeded 0.11 ppm, the number of visits to hospital clinics for childhood asthma or reactive airway disease on the following day was about one-third higher than at other times. Source: White et al., 1994

The validity of these epidemiologic observations has been supported by the results of controlled experimental ozone exposures in human volunteers in which markers of asthma status were measured after ozone and after clean air exposures. In these studies, ozone has been demonstrated to worsen airway inflammation, to increase the airway response to inhaled allergen, and to increase nonspecific airway responsiveness, each of which is likely to indicate worsening asthma.

In several studies, people with asthma exposed to ozone were observed to have a greater influx in polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and larger changes in other markers of airway inflammation than individuals without asthma, suggesting a more intense inflammatory response. In one study ozone increased the numbers of eosinophils found in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of people with asthma. In contrast, eosinophils are not found in the BAL of individuals without asthma as a result of ozone exposure.

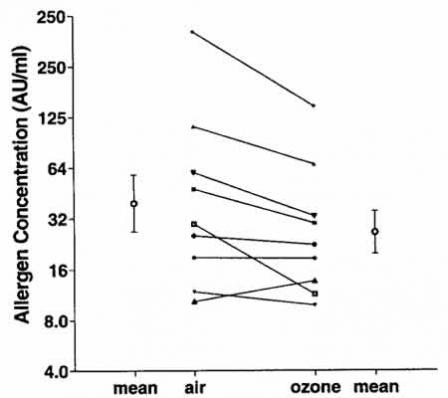

In another study, house dust mite (HDM) sensitive individuals underwent airway challenge with HDM antigen after ozone exposure and after air exposure. As seen in Figure 13, after ozone exposure, the concentration of HDM needed to cause a 20% fall in FEV1 was reduced compared to the air exposure, suggesting that people with asthma would have a greater response to environmental levels of HDM following ozone exposure.

Figure 13: Ozone exposure increases the responsiveness of people with allergic asthma to inhaled house dust mite antigen. The graph shows the airway responsiveness of people with mild allergic asthma to inhaled house dust mite allergen after 7.6-hour exposures to both ozone (0.16 ppm) and filtered air. The point on the far left side of the graph indicates the average concentration of inhaled house dust mite antigen required to produce a 20% decrease in FEV1 following air exposure. The point on the far right indicates the average concentration required to produce a 20% FEV1 decrease following the ozone exposure. On average, after an ozone exposure less antigen is required to produce the FEV1 decrease compared to an air exposure. The points in the center of the graph are the data for the individual participants after both air and ozone exposure. Seven out of nine participants required a lower dose of antigen to produce a 20% FEV1 decrement following the ozone exposure compared to the air exposure. Source: Kehrl et al., 1999

Figure 13: Ozone exposure increases the responsiveness of people with allergic asthma to inhaled house dust mite antigen. The graph shows the airway responsiveness of people with mild allergic asthma to inhaled house dust mite allergen after 7.6-hour exposures to both ozone (0.16 ppm) and filtered air. The point on the far left side of the graph indicates the average concentration of inhaled house dust mite antigen required to produce a 20% decrease in FEV1 following air exposure. The point on the far right indicates the average concentration required to produce a 20% FEV1 decrease following the ozone exposure. On average, after an ozone exposure less antigen is required to produce the FEV1 decrease compared to an air exposure. The points in the center of the graph are the data for the individual participants after both air and ozone exposure. Seven out of nine participants required a lower dose of antigen to produce a 20% FEV1 decrement following the ozone exposure compared to the air exposure. Source: Kehrl et al., 1999

Many studies have demonstrated that nonspecific airway responsiveness is greater following ozone exposure. Overall, these experimental findings in humans and laboratory animals are consistent with ozone causing an increase in asthma severity and, taken together, provide a plausible biological mechanism for the epidemiological observations. This suggests that the observed relationships between ambient ozone exposure and the higher probability of experiencing an asthma attack and other manifestations of worsening asthma are causal.

COPD and other chronic respiratory disease

Epidemiologic studies have had little statistical power to detect relationships between other subcategories of respiratory disease and ozone because of the small numbers of hospitalizations relative to total respiratory or asthma admissions. COPD is the one other respiratory disease for which a relationship has been observed between ozone and hospital admission; albeit in only a relatively few studies. In controlled laboratory exposures, patients with COPD have also been observed to experience small decrements in arterial blood oxygen saturation following 2-hour exposures to 300 ppb with light exercise. Although it is not clear whether these small changes in oxygen saturation in response to relatively high ozone concentrations are sufficient to contribute to an exacerbation of COPD which results in hospitalization, prudence suggests that individuals with COPD and other chronic respiratory diseases should avoid strenuous outdoor activity on days when ambient ozone concentrations are high.