Chinook Salmon

Summary

Declining

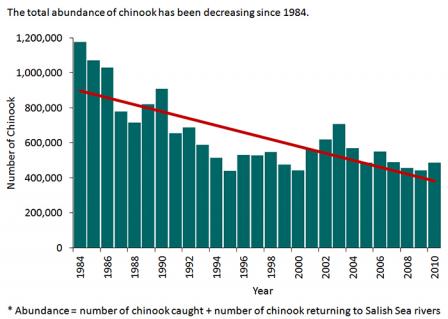

Chinook salmon populations are down 60% since the Pacific Salmon Commission began tracking salmon data in 1984.

Salmon are an iconic species of the Salish Sea. They play a critical role in supporting and maintaining ecological health, and in the social fabric of First Nations and tribal culture.

Strong commercial and recreational salmon fisheries also make salmon an important economic engine for the region.

Chinook (Onchorhychus tshawytscha) are the largest salmon, and are commonly known as "Kings" or "Tyee" (which means "chief" in Chinook jargon).

- Learn other traditional names for Chinook salmon

Chinook salmon are known by many names throughout the Salish Sea and around the world.

- Blackmouth (USA)

- K'with'thet (Salish)

- K'wolexw (Salish)

- King salmon (USA, Canada)

- Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Latin)

- Sa aeup (Nuuchahnulth)

- Sa-cin (Nuuchahnulth)

- Schaanexw (Salish)

- Shamet skelex (Salish)

- Shmexwalsh (Salish)

- Sinaech (Salish)

- Sk'wel'eng's schaanexw (Salish)

- Slhop' schaanexw (Salish)

- Spak'ws schaanexw (Salish)

- Spring salmon (USA, Canada, Australia)

- St'thokwi (Salish)

- Su-ha (Nuuchahnulth)

- Tyee salmon (Canada, USA)

- Learn about Chinook salmon ecology and life history

The Salish Sea is home to seven different species of Pacific Salmonids:

- Chinook salmon

- Coho salmon (also called silver salmon)

- Chum salmon (also called dog salmon)

- Sockeye salmon (also called red salmon)

- Pink salmon (also called humpies)

- Steelhead trout

- Cutthroat trout

Chinook are distinguished by small black spots on both lobes of their tail fin, and black gums in their lower jaw. Their flesh is variable in color, ranging from white through shades of pink to red.

Like other salmonids, Chinook salmon are anadromous and semelparous. They are born in fresh water, spend much of their life at sea, and then return to fresh water to spawn (this is called anadromous). They die after spawning once (this is called semelparous). However, Chinook vary from other salmonids in their age at seaward migration, length of residence in freshwater, estuaries and the ocean, distribution and migration in the ocean and the age and season of migration for spawning.

What's happening?

Just over 485,000 Chinook salmon were reported to be in the Salish Sea in 2010 (source: Pacific Salmon Commission - see chart below). This is a 60% reduction in Chinook abundance since the Commission began tracking salmon data in 1984.

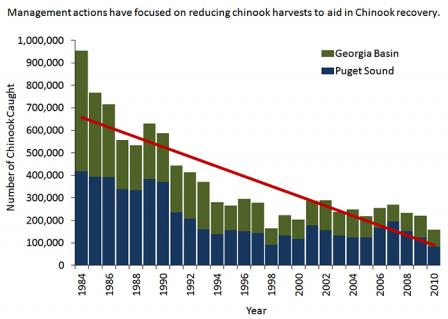

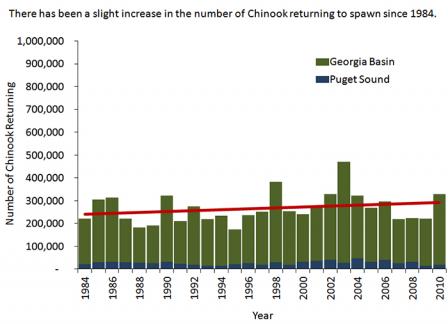

However, there's been a 29% reduction in the number of harvested salmon and a 30% increase in the number of spawning salmon since 1999 when Puget Sound Chinook were listed as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

- View charts showing Chinook abundance, harvest, and return rates since 1984

- Learn more about what's happening

Puget Sound was once home to larger populations of Chinook and other salmon, with a greater diversity of traits than populations existing today. Only 22 of at least 37 historic Chinook populations remain in this ecosystem. The remaining Chinook salmon are only 10% of their historic numbers, with some populations as low as 1% of their historic peak. The decline in salmon is closely associated with the decline in the health of Puget Sound.

The importance of salmon to coastal First Nations and tribes is evident in every coastal archaeological dig in the Salish Sea ecosystem, dating back thousands of years. Salmon had been a constant and reliable part of the Coast Salish diet and religious practices. Reports suggest that Aboriginal harvest rates were not enough to depress salmon populations, but rather, that Aboriginal fishing practices actually amplified salmon abundance.

Why is it important?

Salmon provide food for a variety of wildlife, from bald eagles to killer whales to grizzly bears. Because salmon die after spawning, their carcasses also provide abundant food and nutrients to plants and animals, including tiny aquatic insects and other invertebrates that in turn provide food for other animals.

During their life cycle, salmon transfer energy and nutrients between the Pacific Ocean and freshwater and land habitats. Since Chinook are the largest salmonid, they contribute the largest amount of biomass (organic matter) per fish to the ecosystem. In fact, in areas that have experienced dramatic declines in salmon, there is a measurable deficit of nutrients to help support the ecosystem.

- Learn more about why it's important

Economic Impact

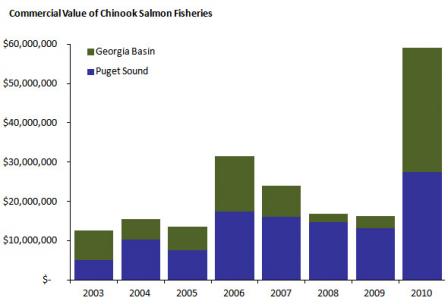

Commercial salmon fisheries in the Salish Sea were worth over $59 million in 2010, driven by an unusually high catch rate that year. From 2003 to 2009, the value ranged from $12.6 to $31.5 million (see chart below).

Annual employment in commercial fishing industry is highly seasonal. In B.C., employment related to commercial fishing was estimated at 2,100 in 2005 - the lowest number recorded in the past two decades - and peaked at 7,000 in 1989. The B.C. fish processing industry employed 3,700 people in 2005, and peaked at 6,000 in 2000.

In Washington, employment related to commercial and recreational fisheries (including harvesters, processors, distributors) was estimated at over 23,000 people in 2009.

Recreational salmon fisheries in the Salish Sea also play important economic and social roles for residents and visitors to the region. Chinook are among the most prized recreational fish. In 2005, sport fishing in B.C. generated $248 million, plus an additional $46 million through associated activities - such as shopping or visits to other attractions by visiting anglers. Sport fishing-related activities employed 7,700 in B.C. in 2005, making it the single largest employer in the fisheries and aquaculture sector.

In Washington, recreational fishing in Puget Sound is conservatively valued at $57 million a year. In 2009, the number of jobs directly linked to recreational fisheries was estimated to be over 3,500 people - supporting over 200,000 resident and visiting anglers.

Why is it happening?

The steep decline in Chinook salmon is associated with three main factors:

- Habitat change.

- Harvest rates.

- Hatchery influence.

Additional factors increasingly recognized as contributing to declining salmon populations include climate change, ocean conditions, and marine mammal interactions.

- Learn more about why it's happening

Habitat Change

Since Chinook habitat spans such a large area - from freshwater to the ocean - they are more likely to be impacted by changes in habitat. Chinook abundance in the Salish Sea ecosystem has decreased as timber harvest, agriculture, urbanization and coastal modifications have impacted the quality and quantity of salmon habitat.

Harvest Rates

From 1975 to 2010, almost 20 million Chinook have been harvested for commercial, sport or subsistence and ceremonial fisheries. Though harvest rates have been decreasing over time, it is difficult to estimate sustainable harvest limits.

Hatchery Influence

Hatcheries operate to salvage remaining salmon populations that have been depleted by habitat loss and other factors. However, hatcheries can have negative impacts on remaining wild salmon populations, including loss of natural population identity, increased competition between wild and hatchery stocks, introduction of diseases from hatchery to wild salmon, and physical impacts to migration from the hatchery operations themselves.

Climate Change

Forecasted impacts from climate change on Chinook salmon include habitat changes, such as increased winter flooding, decreased summer and fall stream flows, and increased temperatures in streams and estuaries. Even small shifts in water temperature could alter the timing of migration, reduce growth, reduce availability of oxygen in the water, reduce availability of preferred food sources, and increase the susceptibility to toxins, parasites and disease.

Ocean Conditions

Salmon survival during their first few months at sea is linked to ocean conditions such as surface temperature and salinity (saltiness) - particularly in coastal and estuarine environments. Ocean conditions can also affect food supplies, numbers of predators, and migratory patterns for Chinook salmon. Each of these factors affects marine survival of Chinook and their ability to return to their streams to spawn.

Marine Mammal Interactions

Fewer Chinook means predators that eat salmon have a greater impact on the overall population of Chinook. California sea lions (Zalophus californianus), Pacific harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) and killer whales (Orcinus orca) are known to prey on Chinook in the Salish Sea. Since the mid-1970s, there has been an increase in the seasonal abundance of sea lions and year-round abundance of harbor seals. The number of Southern Resident Killer Whales has decreased and Chinook salmon are their preferred food source over other salmonid species. It is likely that the loss of Chinook abundance is also a factor in the decreased abundance of Orca.

What are we doing about it?

The 1985 Pacific Salmon Treaty Exithelped bring a science-based approach to international salmon conservation and harvest sharing.

In 2009, a fund was established to lessen the impacts of harvest reductions, support the coded wire tag program (for salmon identification), improve analytical models, and implement individual stock-based management fisheries.

- Learn more about what we're doing

In Canada

In 2011, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) launched a "license retirement" program to reduce harvests of Chinook salmon, including areas within the Canadian portion of the Salish Sea.In 2005, the DFO also released its Wild Salmon Policy to conserve wild salmon and their habitat. The policy aims to safeguard the genetic diversity of wild salmon populations, maintain habitat and ecosystem integrity, and manage fisheries for sustainable benefits.

In the U.S.

In 2008, the Puget Sound Partnership was designated to serve as the regional salmon recovery organization for most Puget Sound salmon species. The Partnership implements its Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Plan by working with local stakeholders and communities, tribes, businesses, and state and federal agencies to protect and restore habitat, raise public awareness, reform hatchery management, assure integration of harvest practices, and develop a monitoring and adaptive management strategy to help track and assess efforts to recover salmon in Puget Sound.

U.S.-Canada Collaboration

The Salish Sea Marine Survival Project is a research project to improve our understanding about the weak survival rates of juvenile salmon. The project brings together U.S. and Canadian experts from federal, state and provincial agencies, tribes and First Nations, and academic and nonprofit organizations including Long Live the Kings in Washington and the Pacific Salmon Foundation in B.C. The project was started in 2012 to evaluate potential stressors on juvenile salmon survival, and help develop science-based solutions to guide improvements in salmon management. As of August 2013, the project is transitioning to a 5-year research phase which will begin in earnest in 2014. Research conclusions and management insights are expected by 2019.

Related Projects

- Puget Sound Recovery Atlas Exit - An interactive map showing conservation and restoration projects in Puget Sound

Five things you can do to help

- Keep streams shaded. Trees and native vegetation along shorelines keep the water cool for fish and help stabilize the banks from erosion. Help protect these types of areas in your community and watch for stream restoration projects and opportunities.

- Keep litter and trash out of streams. Trash can pile up on logs, sticks and other debris and block water flow. Summer is the best time for in-stream cleanup to reduce impacts to key salmon life-cycle stages which typically occur in spring and fall.

- Help protect natural shorelines, wetlands and floodplains in your community. These habitats are extremely valuable to both salmon and people.

- Look for sustainably-harvested salmon at your local supermarket or favorite restaurant.

- Get to know your local watershed group and volunteer to get involved.

Learn more about this topic

- Pacific Salmon Commission

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada - Salmonid Enhancement Program

- Pacific Fishery Management Council

- NOAA Fisheries Salmon and Steelhead

- Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

- Washington Dept. of Fish and Wildlife "SalmonScape" Mapping System

- Puget Sound Partnership Vital Signs - Chinook Salmon

- Salish Sea Marine Survival Project

Scientific references

- H. Heine in Groot, C. and L. Margolis. 1991. Pacific Salmon Life Histories. UBC Press. Vancouver, BC.

- Pacific Salmon Commission. 2011. 2010 Annual Report of Catches and Escapements. Report TCChinook (11)-2. Joint Chinook Technical Committee Report. Accessed May 28, 2012.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011- Information Document to Assist Development of a Fraser Chinook Management Plan. Draft for Discussion Purposes (PDF) (81 pp, 41KB).

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 1999. Fraser River Chinook Salmon. DFO Science Stock Status Report D6-11 (1999)(PDF) (7 pp, 1MB). Delta, BC.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 1999. Lower Strait of Georgia Chinook Salmon. DFO Science Stock Status Report D6-12 (1999)(PDF) (7 pp, 83KB). Nanaimo, BC.

- More references

- Stalberg, H.C., Lauzier, R.B., MacIsaac, E.A., Porter, M., and Murray, C. 2009. Canada’s Policy for Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon: Stream, lake, and estuarine habitat indicators. Can. Manuscr. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2859: xiii + 135p.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2005. Canada’s Policy for Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon. Vancouver, BC. ISBN 0-662-40538-2. Catalogue Number Fs23-476/2005E.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2012. General Information about the Pacific Salmon Treaty Voluntary Salmon Troll Licence Retirement Program. Spring 2012. Vancouver, BC.

- Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Fish Ticket Management Team, 2011.

- NOAA Fisheries. Fisheries Economics of the U.S. Accessed January 2011.

- NOAA Fisheries. 2011. 2011 Report to Congress. Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund FY 2000-2010 (PDF) (16 pp, 3.7MB). Portland, Oregon. 16p.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2005. Endangered and Threatened Species; Designation of Critical Habitat for 12 Evolutionarily Significant Species of West Coast Salmon and Steelhead in Washington, Oregon and Idaho; Final Rule. 50 CFR Part 226. Federal Register Volume 70 Number 170 (PDF) (50 pp, 331KB).

- Washington Department of Ecology. 2008. Focus on Puget Sound - Economic Facts (PDF) (2 pp, 108K).

- Long Live the Kings. 2013. Salish Sea Marine Survival: What are the Causes of Salmon Decline in the Salish Sea?