Swimming Beaches

Summary

Neutral

Overall, nearly three-quarters of swimming beaches in the Salish Sea consistently meet water quality standards.

Access to clean swimming beaches contributes to the high quality of life we enjoy in this region. It's also an indicator of water quality.

Bacteria found in human and animal feces (poop) can cause serious health problems if the levels are above water quality standards, leading to reduced access to swimming beaches.

This indicator tracks the percentage of swimming beaches in the Salish Sea that consistently meet water quality standards through the swimming season.

What's happening?

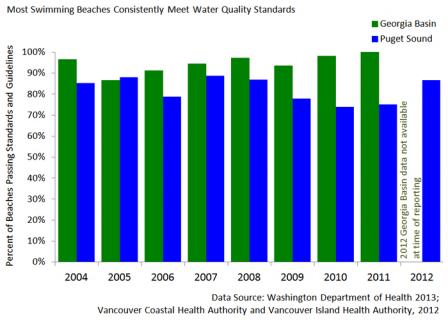

Between 2004 and 2010, over 85% of swimming beaches in Georgia Basin, and over 80% of beaches in Puget Sound consistently met water quality guidelines and standards (see chart below).

In 2011, all beaches in the Georgia Basin met Canadian water quality guidelines for recreation (see Table 1 below - data for 2012 were not yet available at time of reporting).

In Puget Sound, eight swimming beaches (out of the 60 beaches monitored) exceeded water quality standards more than once through the 2012 swimming season (see Table 2 below).

| Year | # of Beaches that Failed Standards | # of Beaches Sampled |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 1 | 30 |

| 2005 | 4 | 30 |

| 2006 | 3 | 34 |

| 2007 | 2 | 36 |

| 2008 | 1 | 37 |

| 2009 | 3 | 46 |

| 2010 | 1 | 56 |

| 2011 | 0 | 64 |

| Year | # of Beaches that Failed Standards | # of Beaches Sampled |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 10 | 68 |

| 2005 | 8 | 67 |

| 2006 | 15 | 71 |

| 2007 | 7 | 62 |

| 2008 | 7 | 53 |

| 2009 | 15 | 68 |

| 2010 | 12 | 46 |

| 2011 | 19 | 76 |

| 2012 | 8 | 60 |

- Learn more about what's happening

What are we actually measuring?

Fecal coliform bacteria are present in virtually all warm-blooded animals, including humans. These bacteria generally do not make people sick, but high levels of fecal coliform in the water means that illness-causing bacteria – which are harder to measure – are also likely present.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) represent about 97% of all the coliform bacteria in human feces, which makes them an excellent indicator of fecal contamination.

Another form of bacteria, Enterococci, survive longer than fecal coliforms in marine water. This type of bacteria is useful to measure when the source of fecal contamination is further from the swimming area. A strong correlation has been demonstrated between the concentration of Enterococci in marine waters and the risk of gastrointestinal infection.

What are the benchmarks?

Different benchmarks are used to interpret water quality data sampled from Georgia Basin and Puget Sound.

Georgia Basin

Water samples taken from swimming beaches in Georgia Basin are tested for levels of E. coli and compared to Canadian Water Quality Guidelines which require that:

- E. coli levels must not exceed 200 bacterial colonies/ 100mL for the average (geometric mean) of at least 5 samples, taken during a period not to exceed 30 days.

Puget Sound

Water samples taken from swimming beaches in Puget Sound are tested for levels of Enterococcus, though fecal coliform bacteria are also sampled at some beaches. Samples are compared to Washington's Water Quality Standards which require that:

- Enterococci levels must not exceed a geometric mean of 70 bacterial colonies/100 mL, with not more than 10 percent of all samples (or any single sample when less than ten sample points exist) obtained for calculating the geometric mean value exceeding 208 colonies/100 mL

- E. coli levels must not exceed a geometric mean of 14 bacterial colonies/100 mL, with not more than 10 percent of all samples (or any single sample when less than ten sample points exist) obtained for calculating the geometric mean value exceeding 43 colonies/100 mL

Why is it important?

Clean swimming beaches are an important part of the quality of life in this region.

Swimming, diving, or wading in water contaminated with fecal bacteria can result in gastrointestinal illness (such as diarrhea or vomiting), respiratory illness, and other health problems. Skin, ear, eye, sinus, and wound infections can also be caused by contact with contaminated water.

Why is it happening?

Fecal contamination at swimming beaches can be caused by a number of issues, including:

- Malfunctioning sewage treatment plants and discharges from combined sewers.

- Improperly maintained septic systems.

- Sewage from recreational boaters.

- Rain water runoff carrying pet and other animal waste.

- High number of swimmers.

What are we doing about it?

Agencies on both sides of the border routinely monitor recreational beaches during the swimming season and post beach advisories if water is unhealthy for swimming. We're also taking actions to help reduce the causes of beach closures due to high levels of bacteria.

- Learn more about what we're doing

Below are some examples of programs that are helping protect public swimming beaches and reduce causes of beach closures:

- In Puget Sound, the Beach Environmental Assessment, Communication, and Health (BEACH) Program is led by the Washington State Departments of Ecology and Health along with county and local agencies, tribes, and volunteers. The BEACH Program monitors high-risk beaches for bacteria and notifies the public when bacteria levels are at unhealthy levels.

- o The Washington Department of Health helps support Pollution Identification and Correction (PIC) programs in six Puget Sound counties. This helps local jurisdictions monitor and notify the public about bacterial pollution at recreational beaches, and also helps support local corrective actions needed from on-site sewage systems and farms.

- In Metro Vancouver, and throughout Puget Sound, construction of new combined sewer-stormwater systems is not allowed. These types of systems (also called Combined Sewer Overflows, or CSOs) can cause serious water pollution problems due to overflows during rain storms because they collect both sewage and stormwater runoff in a single pipe system. Existing combined sewers in Metro Vancouver will be replaced by separate sanitary and storm sewers through infrastructure and sewer capacity upgrading programs.

- In Georgia Basin, a number of recreational boating areas have been designated as "no discharge zones." An eco-rating system has also been developed for marinas, including information about pumpout stations for boaters. In Puget Sound, agencies are also discussing the use of no discharge zones.

Five things you can do to help

- Scoop your pet's poop. Pet waste is full of bacteria that can get washed into waterways and make people sick from swimming in the water or if they eat contaminated shellfish. Scoop it, bag it, and place it in the trash.

- If you're a boater, manage your sewage wastes properly. Do not discharge treated or untreated sewage into our waterways. Use sewage pumpout stations provided at many marinas as a free or low cost service.

- If your home or business uses a septic system, take time to learn how your system works and keep it properly maintained. Ask for maintenance advice from your local health agency.

- If you keep livestock, follow manure management practices. Contact your local conservation agency for technical assistance.

- Keep beaches safe by always using toilet facilities and throwing used diapers in the trash.

Learn more about this topic

The following links exit the site Exit

- Washington Dept. of Health - Swimming Beach Advisories

- Washington's Environmental Assessment, Communication and Health (BEACH) Program

- Puget Sound Partnership Vital Signs - Swimming Beaches

- Health Canada - Recreational Water

- Vancouver Coastal Health - Beach Water Quality Reports

- Vancouver Island Health Authority - Beach Reports

Scientific references

The following links exit the site Exit

- Environmental Protection Agency. 2003. Bacterial Water Quality Standards for Recreational Waters (Freshwater and Marine Waters) Status Report. June 2003. EPA-823-R-03-008. Washington, DC.

- Health Canada. 1992. Guidelines for Canadian Recreational Water Quality. Ottawa, Ontario.

- Health Canada. 2012. Guidelines for Canadian Recreational Water Quality. Ottawa, Ontario.