Step 1. Define the Case

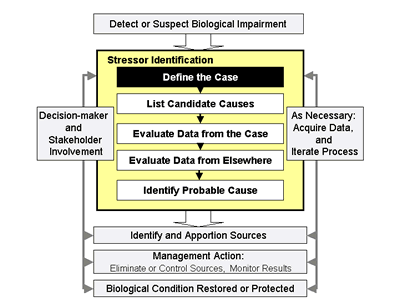

The Stressor Identification process begins by defining the subject for analysis (i.e., the case, Figure 1-1). This is accomplished by determining the investigation’s geographic scope and the effects to be analyzed. The case definition is foundational for causal analysis: it influences what information is assembled, which causes are considered and how conclusions are presented. For this reason, it is important to get input from managers and stakeholders at this early stage.

Figure 1-1. Illustration of where Step 1: Define the Case fits into the Stressor Identification process.Causal analysis is triggered by the observation of a biological effect, including:

Figure 1-1. Illustration of where Step 1: Define the Case fits into the Stressor Identification process.Causal analysis is triggered by the observation of a biological effect, including:- Kills of fish, invertebrates, plants, domestic animals, or wildlife;

- Anomalies in any life form, such as tumors, lesions, parasites, or disease;

- Changes in community structure, such as loss of species or shifts in species abundance (e.g., increased algal blooms, loss of mussel species, increases in tolerant species);

- Response of indicators designed to monitor or detect biological condition, such as the Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI) or the Invertebrate Community Index (ICI);

- Changes in organism behavior;

- Changes in population structure, such as population age or size distribution;

- Changes in ecosystem function, such as nutrient cycles, respiration, or photosynthetic rates;

- Changes in the area or pattern of different ecosystems, such as shrinking wetlands or increased sandbar habitats.

In many cases, the observed biological effects are linked to a biological impairment as defined by a regulatory authority. For example, a stream reach may not meet designated use standards (e.g., fishing) or the specific aquatic life-use class designation assigned by the state.

The first part of defining the case involves defining both the biological impairment and the specific biological effects that led to impairment. For example, as mentioned above, the biological impairment triggering causal analysis may be failure to meet a state's "Class C" water quality standards. The specific biological effects leading to impairment may be decreases in brook trout or decreases in abundance of larval mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies (EPT taxa).

Describing the impairment in terms of what is actually happening biologically makes it easier for you to consider the mechanisms behind the impairment. This also allows you to draw on supporting evidence from other areas (e.g., similar situations in other locales, scientific literature, etc.).

The second part of defining the case is determining its geographic scope. The geographic scope of the case has two parts. First is the impaired stream reach itself (or similar unit). Second is sites within the system (the same stream, watershed, bay, or reservoir) that are unimpaired or impaired differently and can be used for comparison.

Whenever possible, all locations within a case should be part of the same system. They also should be located relatively close together, and aside from anthropogenic effects, should be as similar as possible physically, chemically and biologically. Developing a map of the areas making up the case may make it easier for you to clearly outline the case's geographic scope.

The third part of defining the case is describing the assessment's objectives. Objectives are influenced by the management context of the investigation, and often focus on identifying which of many candidate causes are limiting biological condition.

Once the case has been defined, you move on to Step 2: List Candidate Causes.

In-Depth Look

Each causal assessment focuses on a specific impairment or group of similar impairments collectively referred to as the case.

The case has two components. First, it includes the impaired location. For streams, this is often defined as a reach; for lakes or estuaries, it could be a defined part of the system. Second, the case includes other sites within the same aquatic system that are either not impaired, or are impaired in a different way. These other sites can be used as positive or negative references (i.e., sites used for comparison). All locations within a case must be spatially associated (in the same stream, watershed, bay, reservoir, etc.). In addition, they should be similar physically, chemically, and biologically, except for anthropogenic effects. That is, if there were no anthropogenic effects, the biota should be similar at all sites in the case—the case should be a single ecological system. The acceptable degree of dissimilarity depends on the scale of the assessment. Assessments of extensive impairments imply more biological, chemical and physical variance due to stream gradients, differences in geological substrates, and other factors.

The case is defined by carefully describing the impairment, the specific effects that have been observed, the geographic extent of the impairment, and regulatory and other factors that influence the objectives of the investigation. Relevant references also should be compiled as the investigation begins.

Describe the Impairment

In addition to describing the impairment, it is useful to prepare a background statement describing how the biological impairment was identified. For example, it might be appropriate to refer to a numerical or narrative biocriterion, or to a reference condition that has been created for this type of waterbody, including the documentation for its derivation. If conditions are below expectations, it is important to discuss the quality or condition of the stream in relation to the quality or condition of other streams in the area, or to the same stream in other places or at other times. Including photographs of the waterbody with the descriptive statement can provide visual evidence of a lost resource, and can later be used in describing potential pathways that may have led to the impairment.

Equally important are photographs of what the resource could be like (e.g., taken from other locations), what it used to be like, or what valued attributes are still retained.

Identify Specific Effects

Define the Geographic Area

Define the Objectives of the Investigation

- The regulatory context (you should document any regulatory authorities involved and discuss the regulatory requirement for making a causal determination of the impairment),

- The purpose of the investigation,

- The relative importance of stressors emanating from outside the watershed,

- Stakeholder expectations and interests (advice on engaging stakeholders can be found in Watershed Academy's Getting In Step Guide),

- Logistical constraints,

- Cost,

- Personnel, and

- Available data.

If the study is limited by a paucity of data, it still may be appropriate to attempt a causal determination with the available data, and then indicate what additional information is needed to identify the impairment's cause with greater confidence.

Results and Next Steps

-

A definition of the impairment or group of impairments that will be the focus of the investigation,

- A definition of the specific effects that will form the basis of the analysis,

- A description of the geographic extent of the assessment, and

- A statement of the assessment's objectives.

After you develop these products, proceed to Step 2: List Candidate Causes.