Urbanization - Wastewater Inputs

What Are Wastewater Inputs?

Urbanization often involves the input of wastewaters into streams and rivers.

WWTP discharge on Fourmile Creek, IA.

WWTP discharge on Fourmile Creek, IA. Photo courtesy of USGS

- Industrial effluents: permitted discharges from industrial facilities

- Accidental or unpermitted discharges

- Sanitary sewer overflows: wet weather overflows resulting in direct discharge of domestic and other wastewaters into streams and rivers

- Combined sewer overflows (CSOs): wet weather overflows resulting in direct discharge of surface runoff and domestic and other wastewaters into streams and rivers

- Sewer pipes: leakage from broken, blocked or aging infrastructure

- Septic systems: leachate from septic tanks (usually in less densely developed areas)

- Wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents: permitted municipal sewage discharges (Figure 10), treated to varying degrees (Table 3)

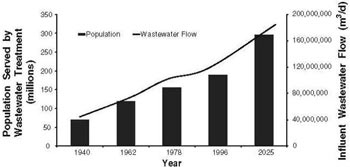

Figure 10. Historical and projected U.S. resident population served by publicly-owned wastewater treatment facilities, and the volume of wastewater flows produced.

Figure 10. Historical and projected U.S. resident population served by publicly-owned wastewater treatment facilities, and the volume of wastewater flows produced.Adapted from U.S. EPA. 2000. Progress in Water Quality: An Evaluation of the National Investment in Municipal Wastewater Treatment. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Washington DC. EPA-832-R-00-008.

| Pollutant | Typical Treatment Efficiencies (% inflow concentrations) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sewage Ponds | Secondary Treatment | Advanced Treatment | |

| BOD* | 50-95 | 95 | 95 |

| Nitrogen | 43–80 | 50 | 87 |

| Phosphorus | 50 | 51 | 85 |

| Suspended solids | 85 | 95 | 95 |

| Metals | Variable | Variable | Variable |

| * BOD = biological oxygen demand. Modified from Baker LA. 2009. New concepts for managing urban pollution. Pp. 69-91 in: Baker LA (ed). The Water Environment of Cities. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. |

|||

Stressors Associated with Wastewater Inputs

- Increased nutrients

[Gücker et al. 2006, Carey and Migliaccio 2009] - Decreased dissolved oxygen (increased biological oxygen demand)

[Ortiz and Puig 2007] - Increased pathogens

[Gibson et al. 1998, Frenzel and Couvillion 2002] - Increased metals (e.g., copper, mercury, cadmium, lead, iron)

[Nedeau et al. 2003] - Increased pharmaceuticals and personal care products

[Kolpin et al. 2002, Watkinson et al. 2009] - Increased toxics (e.g., alkylphenols, pesticides, PAHs)

[Kolpin et al. 2002, Phillips and Chalmers 2009] - Increased dissolved solids (e.g., chloride, sulfate, specific conductance)

[Hur et al. 2007, Rose 2007] - Increased stream discharge

[Nedeau et al. 2003, Barber et al. 2006, Carey and Migliaccio 2009] - Increased temperature

[Nedeau et al. 2003, Kinouchi 2007]

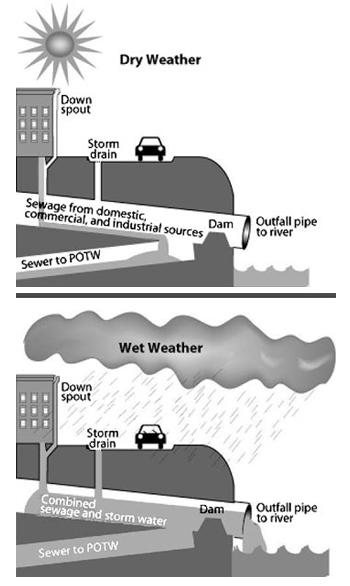

What is a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO)?

A combined sewer system (CSS) is a wastewater collection system that collects and transports sanitary wastewater (domestic sewage, commercial and industrial wastewater) and stormwater to a treatment plant in one pipe. During wet weather, when capacity of the system is exceeded, it discharges untreated wastes directly to surface waters—resulting in a combined sewer overflow (CSO) (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. Schematic of a typical combined sewer system that discharges directly to surface waters during wet weather.

Figure 11. Schematic of a typical combined sewer system that discharges directly to surface waters during wet weather. From U.S. EPA. 2004. Report to Congress: Impacts and Control of CSOs and SSOs. (EPA833R-04�01)

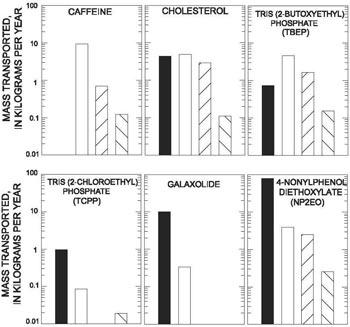

Because CSOs release untreated wastewater, they can contribute pathogens, nutrients, organic carbon, toxic substances and other pollutants to surface waters (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. 2006 annual mass loads for six organic wastewater compounds (OWCs) for the Burlington (VT) Main Wastewater Treatment Plant (filled bar), combined sewer overflow (open bar), and two streams below CSO and WWTP outfalls (striped bars). OWCs on top are highly removed during normal wastewater treatment, while those on bottom are poorly removed.

Figure 12. 2006 annual mass loads for six organic wastewater compounds (OWCs) for the Burlington (VT) Main Wastewater Treatment Plant (filled bar), combined sewer overflow (open bar), and two streams below CSO and WWTP outfalls (striped bars). OWCs on top are highly removed during normal wastewater treatment, while those on bottom are poorly removed. From Phillips P & Chalmers A. 2009. Wastewater effluent, combined sewer overflows, and other sources of organic compounds to Lake Champlain. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 45(1):45-57. Reprinted with permission.

How prevalent are CSOs in the U.S.?

Figure 13. Prevalence of combined sewer systems (CSSs) in the United States.

Figure 13. Prevalence of combined sewer systems (CSSs) in the United States.

- CSSs serve approximately 40 million people, in 772 communities (see Figure 13) (U.S. EPA 2004).

- 828 National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits authorize discharges from 9,350 CSO outfalls (U.S. EPA 2004).

- U.S. EPA estimates that CSOs release approximately 850 billion gallons of untreated wastewater and stormwater each year (U.S. EPA 2004).

CSSs generally have not been constructed since the mid-20th century, and efforts are underway to reduce CSOs in many existing systems (e.g., by separating wastewater and stormwater sewer systems).

Wastewater-Related Enrichment of Streams

WWTP effluents and other sources of domestic wastes (e.g., septic tanks) can subsidize stream ecosystems by increasing nutrient and organic matter inputs to streams (Gücker et al. 2006, Singer and Battin 2007). The amount of enrichment that occurs depends upon the volume of waste discharged, as well as the level of treatment that waste receives.

For example, Singer and Battin (2007) estimated that sewage-derived particulate organic matter (SDPOM) inputs contributed mean annual input fluxes of 108.3 g carbon, 21.7 g nitrogen and 5.9 g phosphorus per day. On average, these inputs represented a 34% increase in seston-bound C and a 29% increase in seston-bound P (although these values were highly variable). Resources in the wastewater-subsidized reach also had higher nutritional quality: % C, % N and % P content were many times greater in SDPOM than in natural seston and benthic fine particulate organic matter (Table 4).

| RESOURCE | % C | % N | % P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Periphyton | 5.9 ± 3.7 8.0 ± 5.0 |

0.8 ± 0.5 1.1 ± 0.6 |

0.15 ± 0.14 0.26 ± 0.15 |

| Seston | 0.6 ± 0.2 1.0 ± 0.3 |

0.1 ± 0.04 0.1 ± 0.05 |

0.021 ± 0.01 0.035 ± 0.02 |

| BFPOM* | 0.2 ± 0.1 0.2 ± 0.1 |

0.02 ± 0.01 0.02 ± 0.01 |

0.01 ± 0.004 0.009 ± 0.004 |

| SDPOM* | - 2.1 ± 0.8 |

- 0.4 ± 0.2 |

- 0.09 ± 0.03 |

| * BFPOM = benthic fine particulate organic matter; SDPOM = sewage-derived particulate organic matter. Modified from Singer GA and Battin TJ. 2007. Anthropogenic subsidies alter stream consumer-resource stoichiometry, biodiversity, and food chains. Ecological Applications 17(2):376-389. |

|||

Figure 14. Daily macroinvertebrate secondary production in reference and wastewater-subsidized reaches of a third-order Austrian stream, by (a) month and (b) functional feeding group.

Figure 14. Daily macroinvertebrate secondary production in reference and wastewater-subsidized reaches of a third-order Austrian stream, by (a) month and (b) functional feeding group.From Singer GA & Battin TJ. 2007. Anthropogenic subsidies alter stream consumer-resource stoichiometry, biodiversity, and food chains. Ecological Applications 17(2):376-389. Reprinted with permission.

These subsidies were incorporated into higher trophic levels, as macroinvertebrate secondary production increased in the wastewater-influenced reach. This enrichment effect was largely due to the response of gatherers and grazer/gatherers (see Figure 14). However, macroinvertebrate diversity and evenness declined in the subsidized reach, indicating enrichment also negatively affected community structure.

Reproductive Effects of WWTP Effluents

Municipal effluents often contain endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which can mimic or interfere with normal hormone signaling in aquatic animals and result in adverse reproductive effects (Jobling and Tyler 2003). Standard wastewater treatment practices typically are not effective at removing these chemicals.

- Natural hormones (e.g., 17β-estradiol)

- Synthetic hormones and other pharmaceuticals (e.g., 17α-ethynlestradiol)

- Pesticides (e.g., diazinon, lindane, atrazine)

- Phthalates

- Toxic metals (e.g., copper, mercury, cadmium)

- Alkylphenols

- Bisphenol A

Photo courtesy of NY DEC.

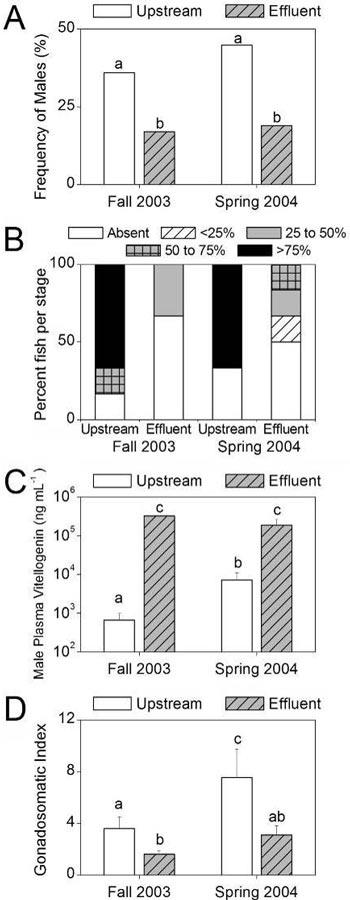

Photo courtesy of NY DEC.  Figure 15. Evidence of reproductive impairment in white suckers collected from sites upstream (upstream) and downstream (effluent) of the Boulder WWTP on Boulder Creek, in terms of (A) % males, (B) sperm abundance in males, (C) plasma vitellogenin concentrations in males, and (D) gonadosomatic index in females.

Figure 15. Evidence of reproductive impairment in white suckers collected from sites upstream (upstream) and downstream (effluent) of the Boulder WWTP on Boulder Creek, in terms of (A) % males, (B) sperm abundance in males, (C) plasma vitellogenin concentrations in males, and (D) gonadosomatic index in females. From Vajda DW et al. 2008. Reproductive disruption in fish downstream from an estrogenic wastewater effluent. Environmental Science & Technology 42:3407-3414. © 2008 American Chemical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Vajda et al. (2008) examined the estrogenic effects of WWTP effluent on white suckers in Boulder Creek, CO. They found that intersex fish—fish that containing both ovarian and testicular tissue—comprised 18-22% of the population downstream of the WWTP outfall, but were not found upstream. Fish downstream of the outfall also had altered sex ratios, reduced sperm production, increased vitellogenin levels (a protein associated with egg development in females) and reduced gonad size (Figure 15).